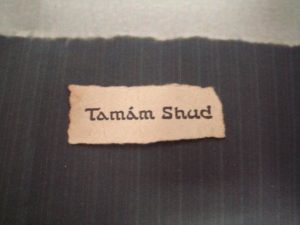

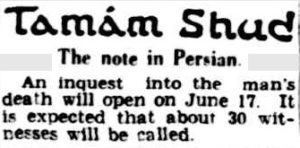

A small remark in the 2013 TV documentary on the Somerton Man seems to have escaped everybody’s attention. I covered the documentary here at the time, but arguably the most interesting bit begins exactly five minutes into the video (transcript as follows):

Kate Thomson: And… there was home life, and there was outside life; but I grew up very much that there’s a barrier between the two, and the two you don’t integrate.

Charles Wooley (voiceover): Today, Kate remembers a mother who was loving, but secretive – so secretive, she now believes that her mother was a Soviet spy.

Kate Thomson: She certainly said once she was teaching English to newly arrived migrants, and at the time there’d been a small group coming from Russia into Australia, and as she said to me, “Ah, I’m surprised that I can still quite understand Russian”.

Charles Wooley (as interviewer): She dropped that bombshell!

Kate Thomson (reported speech): “Yeah, so when did you learn Russian?” “Well, that’s for me to know.”

At first sight, this would seem to achieve nothing apart from hosing a tankerful of petrol onto the already-long-burning conspiracy fires raging beneath the Somerton Man’s pyre-like heap of evidence. But in fact, if you carefully link what Kate Thomson is saying with the history of post-war migrants to Australia, a quite different picture emerges…

Postwar Migrants

I mentioned Ramunas Tarvydas’ (1997) “From Amber Coast to Apple Isle” here back in 2015 when I was first looking at the Electrolytic Zinc Co. of Australia’s mining operations in Rosebury and Risdon (both in Tasmania).

But Tarvydas’ book starts by describing how the very first wave of post-war Balts (i.e. Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians) came to Australia, from their arrival by boat in Fremantle to being allocated work.

The migration scheme had been set up by Arthur Calwell, the Minister for Immigration: because Australia had to “populate or perish” (p.6), migration from the enormous numbers of displaced persons (“DP”s) throughout Europe was – though as politically sensitive an issue then as now – the only real option to try to lift the overall economy.

Tarvydas states that “the initial intake for Australia was restricted to single men and women between the ages of 18 and 40” (p.7). Calwell also put in place a selection policy that favoured those immigrants who happened to be “white-skinned, with blue eyes and blond hair”. Not something that modern historians would look on with any great admiration, let’s say. 🙁

The first group of migrants was known as “the First Transport or Transport I […] 729 men and 114 women” (p.7): these “First Swallows” arrived at Fremantle on 28th November 1947. Four days later, the Balts were put on the HMAS Kanimbla (an Aussie troop-carrier), arriving at Melbourne on 7th December 1947, whereupon they were taken to Bonegilla camp.

Tarvydas asserts that many of the Balts in the first waves “were political refugees rather than immigrants motivated by economics” (p.17): all the same, I’m fairly sure neither account captures the entire picture. Even so, though the USAT General Stuart Heintzelman was supposed to have carried only labourers and similar workers on its first migration run from Europe to Australia, this was clearly not the case. Many of the Balts on board had had professional careers: for example, a lady (Mrs Augustauskas) who had formerly been a pharmacist in Lithuania was initially given a cleaning job at Calvary Hospital (though she later “resat her examinations and became a fully qualified pharmacist” (p.18)).

And so the problem is…

Now that you can see the external history a little more clearly and specifically, do you see the problem with Kate Thomson’s “Soviet Spy” interpretation of what her mother Jo Thomson told her?

The Balts – who made up a very large part of the early waves of immigration into Australia – did not primarily speak Russian. And at that time (and for decades afterwards) there were no waves of Russian-speaking migrants washing onto Aussie shores.

It therefore seems highly likely to me that the migrants Jo Thomson would have been helping to learn English were Balts or possibly Poles, because they were “coming from [what had become annexed into] Russia into Australia”.

Adelaide Migrants

Postwar, the Commonwealth Migration Office was based in Adelaide. And at the beginning of 1948, it was decided that a camp should be built for migrants not too far from Adelaide: this was Woodside, but it was only opened in 1949 (so is out of our date range).

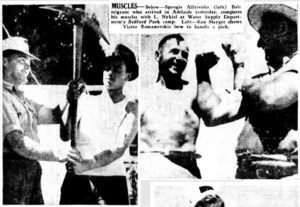

The first sight Adelaideans had of these post-war migrants was in January 1948, when a group of 65 young Balts who had been allocated to work for the Water Supply Department building a new pipeline from Happy Valley Reservoir were accommodated in tents in a paddock in Bedford Park, just south of Adelaide. The press took lots of admiring photos of the strapping young migrants:

But (just as Tarvydas says), they weren’t an obviously good fit for the work that was on offer. A spokesman for the Engineering and Water Supply Department noted: “The Balts are not very keen on pick and shovel work. Most of them are young intellectuals — musicians, draftsmen, surveyors, electricians, medical attendants, engineers, and students. Not one was a laborer by occupation. They were picked from the wrong section of the community from our point of view. We want laborers.”

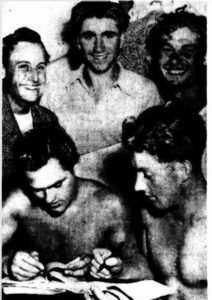

Moreover, it quickly became clear that four weeks of English language classes at Bonegilla hadn’t really been enough: even an op-ed piece of the day thought that the authorities should do something about it (Why oh why? cont. p.94). The young lad Olaf Aerfeldt who was the Bedford Park Balt’s unofficial interpreter had only got there by chance, flipping a coin to choice between Australia and South America (pp.42-46): but they needed to learn English. And – as you can clearly see from this photo – they were anxious to learn, but had no lessons:

At this point, several local people – Mrs and Mrs Lyall Fricker, Peter McDonald and L. A. Tepper – stepped forward to offer their services as volunteer teachers. Though things seemed to have improved somewhat by May 1949.

Finally: I’ll leave the story of how 280 Polish ex-servicemen were discharged in Adelaide on 30th September 1947 for another day: they formed arguably the very first large wave of migrants from mainland Europe, predating the “First Swallows” by a few months. But who’s counting?

And so…

To my eyes, there seems to have probably been only a relatively small window when Jo Thomson would have been helping Adelaide migrants to learn English: late 1947 (when they started to arrive) to early 1950 (when the flow of big migration boats stopped). And there were basically no Russians at that time: mainly Balts and Poles.

If some of the migrants who had formerly lived in Bedford Park were asked if they remembered Nurse Thomson, what would they say? It would be interesting to find out, I think: it might give us a better idea of how that side of her life worked. It probably wouldn’t stop the crackling conspiracy fires (though these may well continue burning, regardless of whatever happens to be uncovered in the future), but it would be good to know, right?

Adelaide Railway Station (Again)

One last thing: while trawling through Trove, I found an Adelaide News article from 20th November 1948 about Balt women working in Adelaide Railway Station that I thought I’d share with you:

[Mrs Natalia Aerfeldt at top, Mrs Vera Plume at bottom left, and Mrs Anna Kirkmann at bottom right]

Three newly arrived Balt women working in the refreshment service at Adelaide Railway Station have husbands training as railway porters here.

A 17-year-old son of one couple is a youth cleaner in the department.

Mrs. Anna Kirkmann, who serves in the dining room, was a bank manager’s private secretary in [Estonia] before the war, and later worked for Unrra.

She arrived here with her husband, Paul Kirkmann, on Thursday as members of a party of 55 Balts.

Other railway family groups besides the Kirkmanns are Mr. Janis Plume, Mrs. Vera Plume, and their son, Roberts, who are

Latvians, and Mr. Bronius Lukavicius and Mrs. Jule Lukavicius, who are Lithuanians.

Mrs. Kirkmann is living with her brother at Glenelg. The married men and Roberts are at the railways hostel at Islington. The other women are in refreshment service quarters at Adelaide Station.

Balts with the railways total nearly 400. Seventy men are porters and cleaners; 100 are being trained for that work, and the remainder are divided between south-east gauge broadening and metropolitan maintenance work.

Mrs. Natalia Aerfeldt, also in this week’s party, is the mother of Olaf Aerfeldt, interpreter at the waterworks camp at Bedford Park. Olaf’s father has gone to Globe Timber Mills, Port Adelaide.

And so there you have it – even by late November 1948, Baltic migrants were working in Adelaide Railway Station, embedding themselves right into the very texture of the Somerton Man’s story.

Who’s to say that he himself wasn’t a migrant?