Though originally published in 1998 and 2003, and most recently published in three volumes in 2013-2014, “Maps, Mystery and Interpretation” is in reality a single (very large) book, the fruits of Geoff Bath’s vast sustained effort to till Oak Island’s unproductive historical soil.

The overall title broadly suggests its three constituent sections, in that Part 1 covers (possibly pirate) treasure maps (“Maps”); Part 2 examines the evidential haze surrounding the Oak Island “Money Pit” mystery (“Mystery”); while Part 3 attempts to put the myriad of pieces together to make sense of them all (“Interpretation”). Simples.

If only the Oak Island mystery itself were as straightforward…

Part 1: Maps

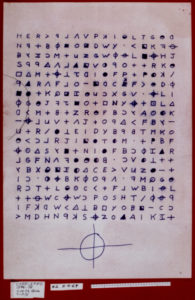

Here, Geoff presents all the “Kidd” maps that Hubert Palmer ended up with, and compares Howlett’s account of them with Wilkins’ account, as well as – and this is the good bit – lots of letters written and received by both Wilkins and Palmer.

I can’t be the only reader to find himself or herself surprised by Bath’s conclusion – that Wilkins essentially got it all just about right, while Howlett got a great deal of it wrong.

All the same, as far as reconstructing the modern history of the Palmer-Kidd maps goes, Geoff’s reasoning here seems very much on the money. I’d say his account gets far closer to what happened than even George Edmunds’ account (stripping both authors’ conclusions out of the picture first).

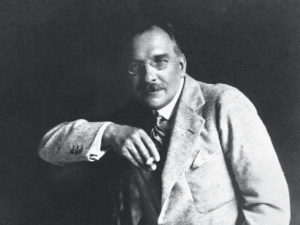

However, Bath gets himself in something of a tangle trying to make sense of the various maps Wilkins originated (both in Part 1 and in Part 3). Was Wilkins adapting maps or documents otherwise unseen, using them as templates for his own creations, or trolling his readers to help him identify mysterious islands? Too often Bath seems content to speculate in a way that paints Wilkins in an almost Svengali-like way, a kind of Andy Warhol of treasure maps.

In reality, I’m far from sure that Wilkins was any closer to historical clarity than we are now. Given that I can’t read more than a handful of pages of his “A Modern Treasure Hunter” without feeling nauseous (the fumes! the bad accents! the ghosts!), I just can’t see Wilkins as anything like a consistently reliable source, even about himself.

Yet one of the most specifically insightful things that emerges from Part One is Bath’s observation that it isn’t necessary for these maps to actually be Kidd’s for them to be independently genuine. That is, the set of maps’ whole association with Kidd might be something that was overlaid onto a (non-Kidd) set of maps: the supposed Kidd link might easily have been added to the mix as a way of “bigging up” someone else’s maps. If this is true (and you don’t have to believe that these are Oak Island maps for it to be so), many of the difficulties that arise when you try to link them to Kidd (e.g. dating, language, etc) disappear.

It’s still hellishly difficult to make sense of these maps, for sure, but Geoff is right to point out that Kidd may well turn out to be part of the problem here, rather than part of the solution or explanation. Something to think about, for certain.

Part 2: Mystery

In my opinion, Oak Island is a wretched, wretched subject, filled with all the slugs and snails of cipher mysteries and not the vaguest flicker of any of the good stuff. It’s a bleak, barren evidential landscape, filled with unconfirmed micro-features briefly noted by a long series of individual investigators, before being quickly razed from the face of the earth by gung-ho treasure hunters. There seems little genuine hope that any faint trace of anything historical or sensible still remains.

Putting the speculative sacred geometry and shapes picked on maps to one side, there are some (though not many) good things in Part Two I didn’t previously know about. Specifically, the idea that tunnels and features might have been dug aligned with the local magnetic compass at that time is quite cool, though obviously something that has been much discussed over the decades.

So I’m terribly sad to have to say that even a perceptive and diligent researcher such as Geoff Bath can make no real difference to this long-standing disaster area. His Part 2 is therefore little more than a Ozymandian monument to the effort and greed sunk in the pursuit of the Money Pit (not that a brass farthing or even so much as a period button has come of it to date).

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away

Part 3: Interpretation

Having struggled through the unpromising desert of the previous part, my expectations as to what Part 3 might bring were fairly low. But as Bath works his way through his interpretation section (repeatedly railing against the pox of untestable hypotheses), something actually rather odd happens.

All of a sudden, he mentions the Venatores (a early 20th century treasure hunting group) and the Particulars (a set of treasure hunting documents collected together by the Venatores). As this enters the picture, it’s as if a curious wave ripples through the whole research fabric: that, contrary to what you might have thought from the two previous books, it’s all not about whether Wilkins was credible or incredible, or whether Hill Cutler was stone cold serious or laughing all the way to the Terminus Road Lloyds Bank in Eastbourne, but instead that there might actually be something behind it all.

That is to say, what emerges – though all too briefly – is a frisson of that wonderfully engaging secret history paranoia where you can just sense stuff going on behind the scenes but which you know you probably won’t ever gain access to.

In the end, Bath’s well-researched and well-written books didn’t manage to persuade me of the existence of a link between the various treasure maps and the Oak Island mystery (and that, indeed, is a hypothesis that would seem to be politically untestable) nor of any kind of geometric cartography plan driving it all. However, it did manage to convince me that the whole Money Pit enterprise might possibly be built not on a vast hole, but instead on a history whose fragmentary parts have been scattered on the winds, and yet which might possibly be reassembled in the future.

It probably won’t happen but… who can say?