During and immediately after World War II, governments everywhere looked with dismay at their non-functioning factories, empty warehouses, and depleted male workforce. Even though the normal economic response to such shortages would be for prices to go up, it was politically vital under the circumstances to prevent profiteering, exploitation, and inflationary pressure from disrupting domestic marketplaces yet further.

In the Commonwealth, legislation was brought in during 1939 to control the prices of many key goods, commodities and supplies: this was known as the Commonwealth Prices Branch. In Australia, this was implemented by appointing a Deputy Price Commissioner for each state, who was tasked with assessing the correct level that specific prices should be. These commissioners were also given the power to investigate and enforce those “pegged” prices (quite independently of the police): the price controls continued until the 1950s.

(Archive material on price control in South Australia is indexed here. For what it’s worth, I’m most interested in D5480.)

Black Markets

While this legislation did (broadly) have the desired effect, the mismatches it introduced between the price and the value of things opened up numerous opportunities for short term black markets to form. One well-known black market was for cars:

15th June 1948, Barrier Miner, page 8:

HINT OF FALL IN USED CAR PRICES

Melbourne.- If control were lifted, prices of used cars would fall and the black market would disappear, men in the trade said today.

Popular American cars would settle to slightly below the former black market price and expensive English cars to below the pegged price, they said.

The pegged price for a 1938 Ford has been £235, and the black market price £450. Buicks, Oldsmobiles, Chevrolets, and Pontiacs might sell for 75 per cent more

than the pegged price.

There was no shortage of English cars, so a 1937 Alvis, now £697, could go down to about £495. The classic English cars of the late 20’s and early 30’s, pegged at about £300, would probably sell at less than £100.

Every car would then find its level. Drivers who had kept their cars in good condition would be able to sell them in direct relation to their values.

Men in the trade said honest secondhand car dealers had almost been forced out of business during the war. Records showed that 90 per cent of all used car sales were on a friend-to-friend basis and they never passed through the trade.

But because you could be fined or go to prison if you bought or sold a car for significantly more than its pegged price, to sell your (say) fancy American car on the black market you would need two separate things: (1) a buyer willing to pay more than the pegged price, and also (2) someone who could supply nice clean paperwork to make the sale appear legitimate if the State Deputy Price Commissioner just happened to come knocking at your door.

And yet because back then cars were both aspirational and hugely expensive (in fact, they cost as much as a small house), so much money was at stake here that it was absolutely inevitable the black market in cars would not only exist, but, well, prosper.

So this is the point where Daphne Page and Prosper Thomson enter the room: specifically, Judge Haslam’s courtroom… I offer the remainder of the post without comment, simply because the judge was able to read the situation quite clearly, even if he didn’t much like what he saw:

Daphne Page vs Prosper Thomson

21st July 1948, Adelaide Advertiser, page 5:

Sequel To Alleged Loan. — Claiming £400, alleged to be the amount of a loan not repaid, Daphne Page, married of South terrace, Adelaide, sued Prosper McTaggart Thomson, hire car proprietor, of Moseley street, Glenelg.

Plaintiff alleged that the sum had been lent to defendant on or about November 27 last year so that he could purchase a new car and then go to Melbourne to sell another car.

Defendant appeared to answer the claim.

In evidence, plaintiff said that before she lent defendant the money she asked for an assurance that she would get it back promptly. She had not obtained a receipt from defendant. After several attempts had been made later to have the loan repaid by Thomson, he had said that the man to whom he had sold the car in Melbourne had paid him by a cheque which had not been met by the bank concerned. When she had proposed taking action against defendant he had said that if she took out a summons she would be “a sorry woman”. He had threatened to report her for “blackmailing.”

In reply to Mr. R. H. Ward, for defendant, the witness denied that anything had ever been said about £900 being paid for the car. She had never told Thomson that she wanted that sum for it. The pegged price of the car was £442.

Part-heard and adjourned until today.

Miss R. P. Mitchell for plaintiff.

22nd July 1948, Adelaide Advertiser, page 5:

BEFORE JUDGE HASLAM:—

Alleged Loan.— The hearing was further adjourned until today of a case in which Daphne Page, married, of South terrace, Adelaide, sued Prosper McTaggart Thomson, hire car proprietor, of Moseley street, Glenelg, for £400, alleged to have been a loan by her to him which be had not repaid.

Page alleged that the loan had been made on or about November 27 last year so that he could purchase a new car and then go to Melbourne to sell another car.

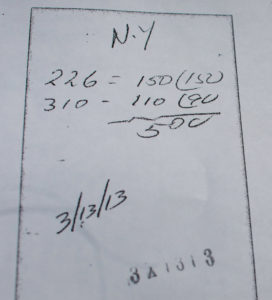

Thomson said that in answer to an advertisement Page had approached him on October 39 with a car to sell. She wanted £900 for it. On November 11 she accepted £850 as the price for the car and said that the RAA had told her that the pegged price was £442.

He drew a cheque for £450 and gave it to Page, who told him she had made out a receipt for £442, the pegged price. Early in December he went to Melbourne to sell a car for another man. On his return to Adelaide be found many messages from Page requesting that he would telephone her. He did not do so, but about a week later met her and told her that he could not pay her the £400 “black market balance” on the car because he had had a cheque returned from a bank.

Page had said she wanted the money urgently, as she had bought a business. Witness “put her off.”

Later, just before a summons was delivered to him, Page had telephoned and asked when he intended to pay the £400. She had spoken affably, but when he told her that he had had advice that he was not required to pay more than the pegged price of the car and did not intend to do so, she had said she would summons him and “make out that the money was a loan.” She had said that she would bring forward “all her family as witnesses.” He hung up the telephone receiver. He had never borrowed money from Page.

Thomson was cross-examined at length by Miss R. F. Mitchell, for Page. Mr. R. H. Ward for Thomson.

23rd July 1948, Adelaide Advertiser, page 5:

BEFORE JUDGE HASLAM: —

Claim Over Car Transaction. —

Judgment was reserved yesterday in a case in which Daphne Page, married, of South terrace, Adelaide, sued Prosper McTaggart Thomson, hire car proprietor, of Moseley street, Glenelg, for £400, alleged to have been a loan by her to him which he had not repaid.

It was alleged by Mrs. Page that the loan had been made on or about November 27 last year so that Thomson could purchase a new car and then go to Melbourne to sell another car.

Thomson denied that he had ever borrowed money from Mrs. Page. He alleged that she had asked £900 for a car, the pegged price of which was £442, and had later agreed to accept £850 for it. After the transaction he had given her a cheque for £450 on account. Mrs. Page had made out a receipt for £442. When she had pressed him, later, for the remaining £400 of the sale, he had told her that, acting upon advice, he did not intend to pay her more than he had. She had then told him that she would summons him and make out that the money at issue was a loan.

Mr. [sic] R. P. Mitchell for plaintiff: Mr. R. H. Ward for defendant.

7th August 1948, Adelaide Advertiser, page 8:

NEW Olds sedan taxi, radio equipped, available weddings, country trips, race meetings, &c.; careful ex-A.I.F. driver. lowest rates. Phone X3239.

17th August 1948, Adelaide News, page 4:

WON CASE BUT NO COSTS ALLOWED

While he gave judgment for defendant in a £400 loan claim in Adelaide Local Court today in a case in which black-marketing of a motor car was mentioned, Judge Haslam refused costs because of defendant’s conduct in the transaction.

Mrs. Daphne Page, of South terrace, City, sued Prosper McTaggart Thomson, hire car proprietor, of Moseley street, Glenelg, for £400 alleged to be the amount of a loan not repaid.

His Honor said if it were not that the Crown would be faced with evidence of plaintiff in the case, he would send the papers to the Attorney-General’s Department with a suggestion that action be taken against defendant for the part he claimed to have taken in an illegal transaction.“Direct conflict”

His Honor said there was a direct conflict between an account which alleged a simple contract loan of £400, made without security and not in writing, and one which set up that the £400 represented the unpaid balance of a black-market transaction.

Evidence was that in November last Mrs. Page had agreed to sell a Packard car for £442, but accepted a cheque for £450, defendant explaining the extra would cover the wireless in the car. Plaintiff gave a receipt for £442, the pegged price.

Plaintiff claimed that in November she lent £400 cash to defendant with which to buy another car in Melbourne. Defendant’s account was that Mrs. Page said her lowest price for her car was £900 and that she afterwards accepted his offer of £850. He said he would give her £450 next day and would want a receipt for the fixed price of £442.

When he gave her the cheque, plaintiff said she did not want a cheque for £450 when the pegged price was £442. He told her not to worry as the unexpired registration and insurance would cover the £8 difference.Borrowing denied

Defendant said in evidence he did not pay the £400 balance and never intended to. He was advised of a new car being ready for delivery in November, but denied having borrowed £400 or any amount from Mrs. Page.

His Honor said there was little support for Mrs. Page’s account as to the terms on which her car was sold. He was of opinion plaintiff had not shown on the balance

of probabilities that any amount was lent to defendant.

Miss R. F. Mitchell appeared for plaintiff, and Mr. R. H. Ward for defendant.

18th August 1948, Adelaide Advertiser, page 5:

Black Market Sale Alleged

BEFORE JUDGE HASLAM:—

In a case arising from the sale of a motor car, in which his Honor yesterday gave Judgment for the purchaser, he refused him costs because of his conduct in the transaction.

The evidence, he said, had produced a direct conflict between an account alleging that a simple contract loan of £400 had been made without writing or security, and one which set up that the money represented the unpaid balance of a black market deal.

The plaintiff, Daphne Page, married woman, of South terrace, Adelaide, claimed £400 from Prosper McTaggart Thomson, hire car proprietor, of Moseley street, Glenelg, alleging the sum to be the amount of a loan not repaid.

It was alleged by the plaintiff that the money had been lent to the defendant on or about November 27 last year, so that he could purchase a new car, and then go to Melbourne to sell another car.

His Honor said he was of opinion that the plaintiff had not shown upon the balance of probabilities that any sum had been lent to the defendant. Were it not for the fact that the Crown would necessarily be faced with the evidence given by plaintiff in the case, he would send the papers relating to the proceedings on to the Attorney-General’s Department, with a suggestion that action sbould be taken against the defendant for the part he had claimed to have taken in an illegal transaction.

There was little to support the plaintiff’s account regarding the terms upon which the car had been sold by her to the defendant, his Honor said. According to her, the price had not been specifically agreed upon, but left to be ascertained by reference to the pegged price, which was £442.

The defendant’s account, his Honor continued, was tbat the plaintiff, after having first told him that £900 was the lowest price she would take for the car, had later accepted his offer of £850 for it. He had paid her £450 by cheque, telling her that he would have to borrow the remaining £400 from a finance company, and adding that he would want a receipt for the pegged price, and the registration to transfer the car into his name. The plaintiff had given him a receipt for £442. The defendant had not paid the £400 balance, and had never intended to do so.

Miss R. F. Mitchell for plaintiff: Mr. R. H. Ward for defendant.