There are now many people who would happily classify themselves as ‘online researchers’. You don’t usually have to peer too far beyond the end of your mouse to see their forum comments, web pages, blog posts, YouTube videos, and occasionally even self-published meisterwerke.

Even though most of these people probably consider that they are engaged in serious research, is that actually the case? What is the difference between serious research and non-serious research? Is there even a difference at all? And (as I heard proposed recently) if there is a difference, surely it’s nothing more than a matter of intelligence, persistence, and luck?

Well… I have to say that that’s a position I can’t agree with at all.

Pay Per Click

Someone clicking on thousands of web pages or running a load of statistical tests can certainly be said to be searching, but this is really not the same thing as researching.

Think about this: how would your behaviour change if every click were to cost you five pounds? Yet in many ways, each click probably does: in terms of the computers you use, the mice you burn up, the broadband you rent, and (arguably the costliest of all) the portion of your life it consumes without returning anything to you. You don’t have to be a full-blown Marxist economist to see that the main thing being eaten away by this kind of activity is you.

The first main difference between searching and researching, then, is that a researcher needs to have an aim to guide his or her actions: every click needs to earn its keep. And the two basic planning tools that help researchers achieve this are research questions and research programmes.

Research Questions

Luckily there is no shortage of web pages that define and discuss research questions, because research questions often have to be included in requests for academic funding. But in many ways, though, given that researching may (being brutally realistic) come to absorb so much of your spare time / life, perhaps you should think of forming a research question as part of making a funding request to your (rational) self. No funding body would ever back someone whose research plan was just to read / try a load of stuff, so why should you back yourself to do the same?

As this web page puts it:

You may have found your topic, but within that topic you must find a question, which identifies what you hope to learn. Finding a question sounds serendipitous, but research questions need to be shaped and crafted.

As a rule, making your research question too general, too wide-ranging or too ‘loose’ is almost always unhelpful, because it means that you will struggle to ever reach an answer for it: too tight and it can come close to being tautologous. There’s a further balance to be had between the availability of evidence and the ‘speculativeness’ of the question: though it has to be said that once you’ve put together your first research question, forming others becomes a lot easier.

Even if your chosen topic is a very evidence-sparse and/or epistemologically uncertain field, you can still form practical research questions (though admittedly doing so can be a little bit less straightforward than in other, more mainstream fields). For example, in the field of Voynich Manuscript research, a partial list of the research questions I personally have pursued over the past 15+ years could contain:

* Using best-in-class Art History dating techniques, when was the Voynich Manuscript made?

* What was the original order of the Voynich Manuscript’s bifolios?

* What did the Voynich Manuscript look like in its ‘alpha’ (original) state?

* Were any parts of the original Voynich text laid down in separate codicological passes?

* Is there a direct mapping relationship between Currier A text structures and Currier B text structures?

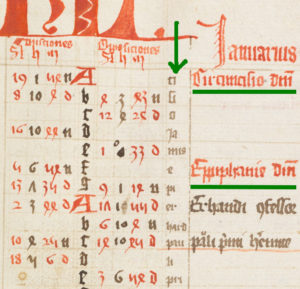

* Is there a relationship between the Voynich Manuscript’s zodiac section and the Volkskalender B family of manuscripts?

* What was the nature of fifteenth century cryptography?

* Might Antonio Averlino have been the author of the Voynich Manuscript?

* What happened between the vellum’s first being written on and the Voynich Manuscript’s reappearance in Prague?

* What did the f116v marginalia originally look like?

* Where did the f116v marginalia handwriting come from?

* Might there have been a relationship between the Voynich Manuscript and the Rosicrucian manifestos?

Note that none of the above is a ‘why’ question: all were specific enough – I hoped when I formed them – for an answer to be reached, though most have still proved to be slower to bring to a fully satisfactory conclusion than I would have chosen. 😐

Note also that a number of the above (though not all) are constructed around hypotheses: while some people are comfortable with hypotheses, others are less so. Regardless, I think it’s important to point out that a good research question need not explicitly include or rely on a hypothesis.

(I’ll leave it as an open question how many other Voynich Manuscript researchers have genuinely formed explicit research questions and research programmes: doubtless you will have your own view on this.)

Research Programmes

Following the logic through, it should be obvious that constructing a research question is only the first half of the planning stage. What you then need to do is to construct a research programme around that research question, to try to help you turn it into a focused series of practical actions you can work your way through in order to reach a worthwhile answer.

Here’s a useful list of questions to help you build this up:

* What literature should you review? (What kind of idiot would not build up a picture of the literature first?)

* What evidence can you rely on in your research?

* What similar research questions have been posed before?

* What answers did those researchers reach? (And what did approach did they follow to reach them?)

* Are there related or parallel fields where similarly-structured research questions have been posed?

* How much time and money do you want to invest in to answer this question?

* What process can you follow to move you closer to an answer?

* Are there others you can usefully collaborate with?

* Are there open source tools or data you can work with (or help develop) that would help?

* If your question is based on an hypothesis, what steps can you take to avoid presuming it is true along the way?

* How can you make sure the answer you reach will be based on causality and not merely on statistical correlation?

Trying to answer these questions (and others like it) should help you work out how you plan to reach a reliable, useful answer to your research question.

Note that “research projects” are the short term subsections you would typically decompose a medium term research programme into so as to make it achievable: project is to programme as chapter is to book.

Planning vs Action

At the end of this whole planning stage, you should have not only a research question that you’re trying to answer, but also a practical plan – i.e. some research means to help you try to reach an answer to your chosen research question.

And so it should be clear that the final difference between searching and researching is that researching requires both a pre-planning phase and some kind of systematic action.

Without conscious pre-planning and some kind of systematic research programme to guide you, you’re searching rather than researching, blindly casting your rod out into a vast evidential ocean. You might occasionally catch a fish, sure: but don’t be surprised if you go home hungry more often than not. :-/