I posted here a few weeks ago about whether the Cisiojanus mnemonic might be in the Voynich zodiac labels, and also about a possible July Cisiojanus crib to look for. Since then I’ve been thinking quite a lot further about this whole topic, and so I thought it was time to post a summary of Voynich labelese, a topic that hasn’t (to my knowledge) yet been covered satisfactorily on the web or in print.

Voynich labelese

Voynich researchers often talk quite loosely about “labelese”, by which they normally mean the variant of the Voynichese ‘language’ that appears in labels, particularly the labels written beside the nymphs in the zodiac section. These seems to operate according to different rules from the rest of the Voynichese text: which is one of the reasons I tell people running tests on Voynichese why they should run them on one section of text at a time (say, Q20 or Q13, or Herbal A pages).

The Voynichese zodiac labels have numerous features that are extremely awkward to account for:

* a disproportionately large number of zodiac labels start with EVA ‘ot’ or ‘ok’. [One recurring suggestion here is that if these represent stars, then one or both of these EVA letter pairs might encipher “Al”, a common star-name prefix which basically means “the” in Arabic.]

* words starting EVA ‘yk-‘ are also more common in zodiac labels than elsewhere

* most (but not all) zodiac labels are surprisingly short.

* many – despite their short length – terminate with EVA ‘-y’.

* a good number of zodiac labels occur multiple times. [This perhaps argues against their obviously being unique names.]

* almost no zodiac labels start with EVA ‘qo-‘

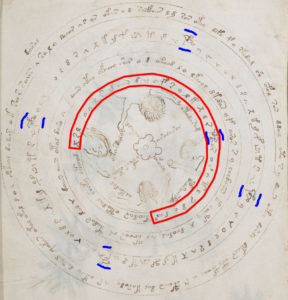

* in many places, the zodiac labels exhibit a particularly strong ‘paired’ structure (e.g. on the Pisces f70v2 page, otolal = ot-ol-al, otaral, otalar, otalam, dolaram, okaram, etc), far more strongly than elsewhere

That is, even though the basic ‘writing system’ seems to be the same in the zodiac labels as elsewhere, there are a number of very good reasons to suspect that something quite different is going on here – though whether that is a different Voynich ‘language’ or a type of content that is radically different from everything else is hard to tell.

Either way, the point remains that we should treat understanding the zodiac labels as a separate challenge to that of understanding other parts of the Voynch manuscript: regardless of whether the differences are semantic, syntactic, or cryptographic, different rules seem to apply here.

Voynich zodiac month names

If you look at 15th century German Volkskalender manuscripts, you’ll notice that their calendars (listing local feasts and saint’s days) typically start on January 1st: and that in those calendars with a zodiac roundel, January is always associated with an Aquarius roundel. Modern astrologically / calendrically astute readers might well wonder why this would be so, because the Sun enters the first degree of Aquarius around 21st January each year: so in fact the Sun is instead travelling through Capricon for most of January.

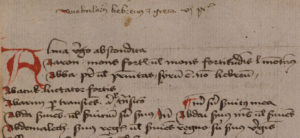

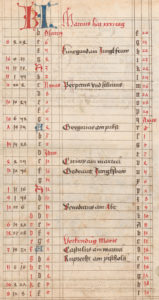

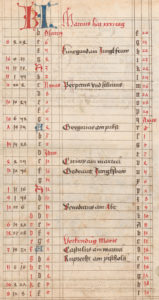

However, if you rewind your clock back to the fifteenth century, you would be using the Julian calendar, where the difference between the real length of the year and the calendrical length of the year had for centuries been causing the dates of the two systems to diverge. And so if we look at this image of the March calendar page from Österreich Nationalbibliotech Cod. 3085 Han. (a Volkskalender B manuscript from 1475 that I was looking at yesterday), we can see the Sun entering Aries on 11th March (rightmost column):

Note also that some Volkskalender authors seem to have got this detail wrong. 🙁

All of which is interesting for the Voynich Manuscript, because the Voynich zodiac month names associate the following month with the zodiac sign, e.g. Pisces is associated with March, not February (as per the Volkskalender), etc. This suggests to me (though doubtless this has been pointed out before, as with everything to do with the Voynich) that the Voynich zodiac month name annotations may well have been added after 1582, when the Grigorian calendar reforms took place.

Voynich labelese revisited

There’s a further point about Voynich labelese which gets mentioned rarely (if at all): in the two places where the 30-element roundels are split into two 15-element halves (dark Aries and light Aries, and light Taurus and dark Taurus), the labels get longer.

This would seem to support the long-proposed observation that Voynich text seems to expand or contract to fit the available space. It also seems to support the late Mark Perakh’s conclusion (from the difference in word length between A and B pages) that some kind of word abbreviation is going on.

And at the same time, even this pattern isn’t completely clear: the dark Aries 15-element roundel has both long labels (“otalchy taramdy”, “oteoeey otal okealar”, “oteo alols araly”) and really short labels (“otaly”), while whereas the light Aries has medium-sized labels, some are short despite there being a much larger space they could have extended into (“oteeol”, “otolchd”, “cheary”). Note also that the two Taurus 15-element roundels both follow the light Aries roundel in this general respect.

It therefore would seem that the most ‘linguistically’ telling individual page in the whole Voynich zodiac section would seem to be the dark Aries page. This is because even though it seems to use essentially the same Voynich labelese ‘language’ as the rest of the zodiac section, the labels are that much longer (or, perhaps, less subject to abbreviation than the other zodiac pages’ labels).

It is therefore an interesting (and very much open) question as to whether the ‘language’ of the text presented by the longer dark Aries labels matches the ‘language’ of the circular text sequences on the same page. If so, we might be able to start to answer the question of whether the Voynich labels are written in the same style of Voynichese as the circular text sequences on the same pages, though (with the exception of most of the dark Aries page) more abbreviated.

Speculation about ok- and ot-

When I wrote “The Curse of the Voynich”, I speculated that ok- / ot- / yk- / yt- might each verbosely encipher a specific letter or idea. For example, in the context of a calendar, we might now consider whether one of more of them might encipher the word “Saint” or “Saints”, a possibility that I hadn’t considered back in 2006.

Yet the more I now look at the Voynich zodiac pages, the more I wonder whether ok- and ot- have any extrinsic meaning at all. In information terms, the more frequently they occur, the more predictable they are, and so the less information they carry: and they certainly do occur very frequently indeed here.

And beyond a certain point, they contain so little information that they could contribute almost nothing to the semantic content, XXnot XXunlike XXadding XXtwo XXcrosses XXto XXthe XXstart XXof XXeach XXword.

So, putting yk- and yt- to one side for the moment, I’m now coming round to the idea that ok- and -ot- might well be operating solely in some “meta domain” (e.g. perhaps selecting between one of two mapping alphabets or dictionaries), and that we would do well to consider all the ok-initial and ot-initial words separately, i.e. that they might present different sets of properties. And moreover, that the remainder of the word is where the semantic content really lies, not in the ok- / ot- prefix prepended to it.

Something to think about, anyway.

Voynich abbreviation revisited

All of which raises another open question to do with abbreviation in the Voynich Manuscript. In most of the places where researchers such as Torsten Timm have invested a lot of time looking at sequences that ‘step’ from one Voynichese word to another (i.e. where ol changes to al), those researchers have often looked for sequences of words that fuzzily match one another.

Yet if there is abbreviation in play in the Voynich Manuscript, the two syntactic (or, arguably, orthographic) mechanisms that speak loudest for this are EVA -y and EVA -dy. If these both signify abbreviation by truncation in some way, then there is surely a strong case for looking for matches not by stepping glyph values, but by abbreviatory matches.

That is, might we do well to instead look for root-matching word sequences (e.g. where “otalchy taramdy” matches “otalcham tary”)? Given that Voynich labelese seems to mix not only labelese but abbreviation too, I suspect that trying to understand labelese without first understanding how Voynichese abbreviation works might well prove to be a waste of time. Just a thought.

Dark Aries, light Aries, and painting

As a final aside, if you find yourself looking at the dark Aries and light Aries images side by side, you may well notice that the two are painted quite differently:

To my mind, the most logical explanation for this is that the colourful painting on the light Aries was done at the start of a separate Quire 11 batch. That is, because Pisces and dark Aries appear at the end of the single long foldout sheet that makes up Quire 10, I suspect that they were originally folded left and so painted at the same time as f69r and f69v (which have broadly the same palette of blues and greens) – f70r1 and f70r2 may therefore well have been left folded inside (i.e. underneath Pisces / f70v2), and so were left untouched by the Quire 10 heavy painter. Quire 11 (which is also a single long foldout sheet, and contains light Aries, the Tauruses, etc) was quite probably painted separately and by a different ‘heavy painter’: moreover, this possibly suggests that the two quires may well not have been physically stitched together at that precise point.

Note that there is an ugly paint contact transfer between the two Aries halves (brown blobs travelling from right to left), but this looks to have been an accidental splodge (probably after stitching) rather than a sign that the two sides were painted while stitched together.