Writer (and University of Bristol PhD student) Gerard Cheshire has recently been asking people to look at his paper “Linguistic missing links: instruction in decrypting, translating and transliterating the only document known to use both proto-Romance language and proto-Italic symbols for its writing system“. (Note that this is actually a draft, but dressed up to look as though it is to be published in “Science Survey (2017) 1” when, as far as I can tell, there is no such journal as “Science Survey”.)

His paper breathlessly reveals that Voynichese is nothing more than Vulgar Latin (though without any obvious grammar or structure). He then proposes a scheme mapping Voynich letters to normal letters (though this lacks “b/f, c/k, ch/sh, g/gh, h/j/ym v/w, x/z” [p.17]), which he then uses to “transliterate” some sentences (though shaped out of strings of words assembled from God-only-knows-how-many different European languages) into something approaching modern-day English. These sentences ‘demonstrate’ that the Voynich Manuscript is (running counter to the radiocarbon dating) actually from the 16th century, and is nothing more than a courtly woman’s health and bathing manual, a fact which every other Voynich Manuscript researcher to date has been too short-sighted to see or recognise, bla bla bla bla bla bla bla.

Errrm… really? Really? Really?

Vulgar Latin

First thing I have to point out is that there is no such (single) thing as Vulgar Latin: rather, the phrase denotes a vast family of vulgar / pidgin / hybrid Latin-ish spoken languages sprawled across all of Europe and over most of a millennium.

Every single version of Vulgar Latin was a purely local affair, nobody spoke them all at the same time – Vulgar Latin wasn’t a universal lingua franca, it was a heterogenous set of hacky vulgar dialects that helped people get by locally. And I simply don’t believe for a moment Cheshire’s implicit claim (completely necessary to his argument, but not expressed anywhere I can see) that this kind of Vulgar Latin had no structure, that each specific instance of Vulgar Latin was no more than language expressed as a diarrhoeal deluge of words that listeners teased meaning out of.

As a result, the entire linguistics mindset running through Cheshire’s paper (i.e. the comparison between a single concerted instance of a script and a vast cloud of unwritten potentialities diffusely surrounding a huge family of languages, each of which is presumed to have no structure) seems utterly wrongheaded.

As such, it makes no sense at all to compare a single slab of written Voynichese text (which gives every sign of having been written in a single time and place) with a wide set of different language potentialities (that, further, were almost never written down, and – further still – would in every instance have had a basic rationale and structure [because that’s how language works] that he requires to be absent).

A Monstrous Mash-up

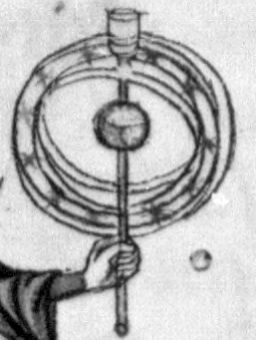

Even though Cheshire puts forward his speculative translations (which he repeatedly calls “transliterations”, as if that somehow brackets out the mile-wide interpretational chasms he repeatedly has to swing across) of several sections of the Voynichese text, I’m going to give as my example here the top three lines of f82v that he discusses on pp.20-21. This is because f82v is a nice, bright, easy-to-read page in the “Balneo” quire (Q13), which means that the various EVA transcriptions speak almost with a single voice:

tokol.olfchedy.qokeedy.qokedal.shol.qotal.otdal.dal.olshedy-{figure}

qokedy.lshedy.qotol.dol.shedy.shedy.dy.dar.otedy.chetedy.lokam-{figure}

dair.ol.chedy.qotedy.qotedy.chsdy.qotal.qoty.qokal.qokedy.lo-{figure}

Cheshire’s own transcription of these lines (according to his conversion-to-letters-scheme) is as follows:

molor orqueina doleina dolinar æor domar om nar nar or æina,

dolina ræina domor nor æina æina na nas omina eimina rolasa,

nais oe eina domina domeina etna domar doma dolar dolina ro.

Let’s take each line apart in turn to see what he’s trying to get at:

molor = mollor = (soften/calm/pacify) [Latin] – because molor (grind/mill/wear) [Latin] “would be inappropriate”

orqueina = ?

doleina = therapeutic [Catalan]

dolina/dolinar = bath/bathe [Romance languages]

æor = ?

domar = to tame/control [Catalan and Portuguese]

om = hom (homine) = man [Latin]

nar nar = foolish/crazy/up-tight [Romansch]

or = ?

æina = wife [Catalan]

Cheshire’s “reasonable transliteration” (i.e. speculative translation) for this first line is: “Calming with therapeutic bathing is always certain to tame the tense man and wife“.

dolina/dolinar = bath/bathe [Romance languages]

ræina (reina) = queen [Romance languages]

domor = [domar] = to tame/control [Catalan and Portuguese]

nor = daughter-in-law [Aromanian]

æina = wife [Catalan]

æina = wife [Catalan]

na = ?

nas = ?

omina = omen [Latin]

eimina = to eliminate [Spanish and Portuguese]

rolasa = ?

His translation of the second line is: “A queen’s bath always relaxes the daughter-in-law and wife to eliminate the omen, for it to happen“.

nais = to begin/commence/create [French]

oe = ?

eina = ?

domina = lady [Latin]

dome[i]na = domain/room [Latin]

etna (ætna) = to heat/burn [Latin/Greek]

domar = to tame/control [Catalan and Portuguese]

doma = ?

dolar = ?

dolina/dolinar = bath/bathe [Romance languages]

ro = abbreviation for rogo = to ask/request [Latin]

His third line of translation runs: “Begin now the method for the lady’s domain, and heat the room to make the bathing smooth, please!”

Cheshire sums up what these three lines mean as follows:

So, the passage appears to be advice for the mother (queen) of a prince to impart to her daughter-in-law as guidance for seducing her son and becoming pregnant.

Like a badly mislabeled lift, this is wrong on so many levels. Nobody reading the above should need to look through Latin, Catalan, Portuguese, Romansch, Aromanian, French, Greek, and “Romance languages” dictionaries to find words to describe this fantastical nonsense. (Though you might find Partridge’s “Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English” most fruitily germane to the task.)

Disastrous Dog’s Dinners

What Cheshire has been seduced by here is the beguiling notion that the numerous textual difficulties that Voynichese presents might all be magically explained away by a wave of the polyglot fairy’s wand, e.g. that the Voynich’s tightly-knit buzz of similar words might simply be a result of a large number of active component languages somehow feeding into the plaintext. However, it should be no surprise that these polyglot sirens appear rather different when you take a closer look at them:

For all the undoubted cleverness of Leo Levitov PhD, his particular polyglot reading of the Voynich was (as seasoned Voynich Manuscript researchers will happily attest) more or less exactly the same kind of dog’s dinner as Cheshire’s is. And this was for exactly the same reason, which is that the Voynich Manuscript’s curious text presents so many different kinds of non-language-like behaviours all at the same time that trying to read it as if it were a simple language (even a polyglot mash-up “simple language”) is never, ever going to work.

Specifically, the kind of challenging textual behaviours I’m talking about here are:

– 1) Low entropy (highly predictable, babble-like text)

– 2) Highly structured letter placement rules (e.g. highly stylized word beginnings and endings)

– 3) Two or more significant language variants

– 4) A surprisingly high (dictionary size) : (corpus size) ratio.

– 5) A generative dictionary (i.e. covering many more permutations than normal languages do)

– 6) Only sporadic word adjacency pattern matches

– 7) Neal keys (both vertical and horizontal)

– 8) Where are common words like “the” and “and”?

– 9) Where are the number shapes, number clusters, or number patterns?

– (etc)

My point here is that while it is possible to construct a proof-of-concept plaintext language to partially get around one or two of these issues, all the other pesky behaviours will then cause that ‘solution’ to sink like a Chicago Mafia whistleblower. This is all pretty much what Elizebeth Friedman was talking about in 1962 about people seeking such solutions being “doomed to utter frustration”: it’s a horrible shame that in 2017 people continue to fail to even begin to grasp what is such a basic message.

In the case of Cheshire, a polyglot Vulgar Latin reading would aim to get around points 4) and 5), but would then collapse in a miserable heap at the hands of all the other points. Anyone following Stephen Bax’s miserable lead to try to come up with their own ingenious linguistic reading of Voynichese should wise up to the whole list, because – unless you are even trying to satisfy all these oddly non-language-like constraints all at the same time – you’re plainly wasting both your own time and that of everyone else you try to convince.

Laughable linguistics

When I read nonsensical papers like this (and I can assure you that this is not an outlier, because there are plenty more of them out there), I feel a deep sadness for historical linguistics. Even for unbelievably bright people such as George Steiner (who at his peak was clearly a hugely inspirational speaker, and whose books oddly summon to mind Ioan Couliano’s syncretic layerings), far too many linguists lard their writing with speculative etymological riffs anyone else would be embarrassed to put their name to, even if they were walking home from a beer festival drunk and wearing a foolish hat. (For his sins, Cheshire throws a fair few of these soggy prawns onto his linguistic barbecue.)

And whenever I see linguistics people rap about Ur-languages while constructing metronomically-timelined millennia-spanning etymology trees (yet again), I just despair. All the while modern linguists can’t construct solid etymologies for the words we use in the 21st century, what chance do historical linguistics people really stand going back X hundred years? Honestly, some things lie beyond the limits of useful reconstruction, and trying to claim otherwise is a collective (and discipline-wide) failure.

To me, the structural problem with historical linguistics, then, is that if you remove all the brazenly bullshit stuff, what little is left is perilously close to a tree-less tundra: it remains an academic discipline, sure, but one whose grasp of history is all too often paper-thin (as is its actual use to historians), and whose pretensions to science are largely laughable.

And so I really don’t think that Gerard Cheshire should feel bad about having ended up down a garden path here, when it’s actually historical linguistics that has marched down that garden path en masse. The entire conceptual toolkit that he brought to bear on the Voynich Manuscript was as much use as a Swiss Army Knife made of soft-set jelly: sorry to have to say it in such flat terms, but the poor bugger never really stood a chance.