A few days ago, my wife suggested that the plant depicted on f36r might be a variety of geranium: on a hunch, I thought I’d compare it with the plants in Fuchs’ famous herbal – and Google quite unexpectedly directed me to a museum in Tuscany.

You see, in 2002 the Aboca Museum in Sansepolcro embarked upon an ambitious programme to bring together, to document, and even to publish its own books on the history of herbal medicine in Tuscany. It even has an online virtual tour (in both English and Italian) of its various collections of herbal-/apothecary-related artefacts (such as maiolica, pestles and mortars, books), though I’d recommend broadband. (I can’t stand their background saxophone music, though, sorry!)

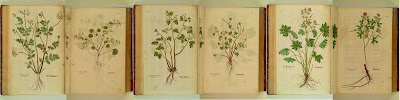

For history lovers, they have also put scans of a number of herbals. Here I’m interested in their online browsable copy of Leonhard Fuchs’ Great Herbal (“De historia stirpium”), though only in 72dpi resolution (boo!). Handily, though, this is searchable by keyword: and for “geranium”, you find that Fuchs included drawings of six varieties of geranium (“geranion” in Greek) on plates 204-209. I pasted the images side by side so that I could compare them properly: this is what it looks like (be warned if you click on it, it’s a 3000-pixel-wide image!)

I think that the best match by far is the third plate (plate 206, “Geranium Tertium”, or “Ruprechtskraut”), as this has a similar curious rootball and a hairy lump” (the crane’s bill, I believe!) just beneath each flower. I put this side-by-side along with a picture of the plant on my neighbour’s front step (thanks Alex!) and the Beinecke’s scan of f36r: and now I’m pretty sold on the idea that this is indeed a geranium (thanks Julie!)

There’s another version from the Biblioteca Riccardiana here, and also an uncoloured version of Fuchs’ plate in Yale’s medical library here (on the left).

It is thought that Fuchs’ “Geranium Tertium” corresponds to the “Geranion Eteron” in Book Three (Roots) of Dioscorides. There, Section 3-131 says:-

“Geranium has a jagged leaf similar to anemone but longer; a root somewhat round, sweet when eaten. A teaspoonful of a decoction (taken as a drink in wine) dissolves swellings of the vulva. It has slender little downy stalks two feet long; leaves like mallow; and on the tops of the wings certain abnormal growths looking upward (like the heads of cranes with the beaks, or the teeth of dogs), but there is no use for it in medicine. It is also called pelonitis, trica, or geranogeron, the Romans call it echinaster, the Africans iesce; it is also called alterum geranium by some, but others call it oxyphyllon, mertryx, myrrhis cardamomum, or origanum. The Magi call it hierobryncas, the Romans, pulmonia, some, cicotria, some, herba gruina, and the Africans, ienk.”

What do you think?