While reading up on the John Titor phenomenon (which Benjamin Kerstein based his Josef6 novel upon), I came across some other great modern hoaxes / self-deceptive phenomena I hadn’t previously been aware of. I decided to briefly explore these, in case I could find parallels I could find with the Voynich Manuscript (thanks to Gordon Rugg, the notion of a “Voynich hoax” has become well entrenched in VMs commentary).

First up is The Case of Kirk Allen from the (somewhat worryingly named) Brainsturbator blog, who in turn took it from Jacques Vallee’s book “Revelations”. This tells the story of a research scientist who compiled a gargantuan mass (200 chapters, 82 scale maps, 61 architectural sketches, 12 genealogical tables, 306 drawings etc) of highly detailed documents that somehow told of his epic life in space – and the psychologist in Baltimore who took on his case.

It’s all fascinatingly delusional stuff, particularly in the way that the psychologist had to sort himself out after having sorted out his patient. The Brainsturbator blogger intersperses the text with small images from the Codex Seraphinianus, whose own unhinged brand of otherworldiness fits the whole tale quite well.

Some have claimed that the Voynich Manuscript is this kind of an object (though meaningless), a kind of cursed intellectual science fiction where the form takes over the content, and where the writing takes over the writer (though several hundred years before Science Fiction became an actual genre, of course). But I’m not convinced: Kirk Allen’s need was for a narrative object to make sense of his life. Though he wrote some sections in his own private shorthand, this was a very secondary aspect of the whole fantasy: he needed to write it in order to link all his delusions together by bringing them all to the surface, not to hide them from himself.

In fact, his whole work was a kind of ‘proto-therapy’, and so ultimately all that the psychiatrist Dr Lindner did was to help steer Kirk Allen towards the logical completion of his workj, at which point its fragility would be revealed and it would all fall away. Though this is what happened, it did take a looooong time.

The second example is UMMO (also from our Brainsturbator friend), a weird European UFO cult that was started as a kind of surreal practical joke by Spaniard Jose Luis Jordan Pena, pretending that Earth had visitors from the Planet UMMO. Thanks to a bit of physics trickery (mainly triboluminescence), many people were taken in by the carefully staged demonstrations of communication with these aliens.

And nobody would have been any wiser, had not one particular crazy sect called “Edelweiss” begun to brand their children with the UMMO emblem: at which point Pena decided that enough was enough, and so ‘fessed up to the whole thing.

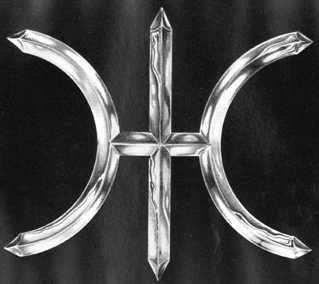

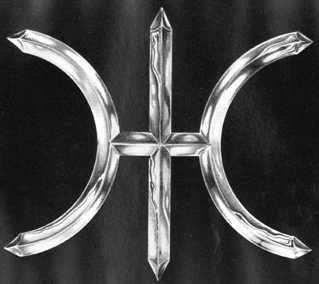

The UMMO emblem (from an Italian site)

The UMMO emblem (from an Italian site)

Now this, like the John Titor phenomenon, was a well-executed hoax, and – given that it required many more people to collaborate over a period of decades to achieve its rather cheeky result – was perhaps even more special.

Was the Voynich Manuscript a hoax? From reading about these actual hoaxes, I’m particularly struck by their storytelling aspect: at each stage, you can say whatever you like, as long you give yourself enough “wriggle room” to embellish and extend in the future. In fact, you can view them as a kind of improvisational storytelling, where the hoaxer picks up the threads of the hoaxee’s disbelief and actively weaves them back into the fabric.

In business school terms, this is a kind of non-formally planned strategy that is interactive, almost to the point of resembling a game: hence the parallels (I’m thinking mainly of UMMO and Dan Burisch here) that emerge with role-playing games. Whereas if you try to impose a hoaxing explanation on top of the Voynich, you pretty much have to accept that its type of game was role-played purely by the maker, without anyone else ever looking at it.

Thirdly, there is the whole Urantia Book phenomenon, which seems to be a kind of strange fake-science channeling thing. This too wove details and objections from the world into a kind of strange religious-like fabric of immense size. Could the VMs contain channelled semi-religious writings, a kind of Renaissance halfway-house between Hildegard of Bingen and the Urantia Book? Again, it doesn’t seem to me to satisfy the need for a narrative explanation, which seems to me to be best (and most powerfully) described as a fabrication, where a collection of unconnected threads are iteratively woven into a single “explanatory fabric”.

And so we come back to the notion of a delusional internal architecture behind the VMs, more like Kirk Allen’s magnum opus: but one where the writer is apparently trying to make something difficult for himself/herself rather than something helpful. But how could that form the basis of a better explanation of the Voynich than “a cipher we cannot yet break”?

I suppose people like Rugg have made hoaxing an intellectual fashion item, a postmodern superficiality that can be cleverly namedropped at parties – oh, didn’t you hear that it’s meaningless? Yet to make this leap of faithlessness, you have to abandon any pretence at trying to read the history of the object, and discard any idea of reconstructing the psychology (or indeed the psychopathy) patiently assembling a complex thing for its own rational reasons. But Rugg’s hoax account seems like a shallow, unidimensional tack to take: sorry, but humans are complex entities, and nothing human is ever that simple.