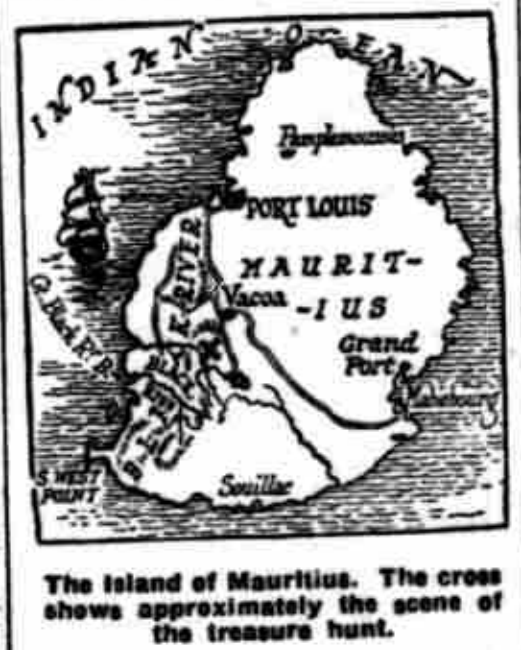

In Part 1 and Part 2, I looked at how early British ‘geophys’ technology and Mauritian treasure hunting dreams converged in the 1920s. But once the Liverpool firm of W. Mansfield & Co had been persuaded by the Klondyke Syndicate to jump into the Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang treasure-hunting fire, I think it’s safe to say that just about all outcomes were going to be bad.

So what did happen next? And who exactly was “Captain Russell”, Mansfield’s main man in Mauritius?

The Death of the Dream

From a short article in the The Daily News (4th February 1927, p.10), we can see almost exactly to the day when Mansfield’s expensive treasure-hunting collaboration with the Klondyke Syndicate ended up:

After several unsuccessful attempts to locate what is known as the “Klondyke Treasure” on this island, Captain Russell, of Liverpool, is returning to England.

It is understood that Captain Russell was sent out by a large Liverpool firm for the purpose of prospecting for precious metal. A staff of 50 men and women, under his control, have been engaged for the past 18 months in elaborate excavations. Each successive attempt has ended in failure, and the expedition has finally decided to abandon the treasure hunt.

The last attempt alone is said to have cost £15,000.

But who was he? For several years, I and others have been trying to find out more about Captain Russell: apart from a few brief newspaper articles (such as the Daily News article above), he seemed to have been almost as hard to find as the Klondyke Treasure itself.

Well, that was the situation until this weekend, when my latest attempt to rake keyword phrases through the British Newspaper Archives at long last yielded what seem to be interesting results…

The Lusitania!

In the Linlithgowshire Gazette of 17th May 1935 p.3 (don’t say I don’t spoil you), I found an article discussing a particularly hi-tech sea expedition to locate the wreck of the Lusitania:

An expedition will set out from the Clyde next month to the wreck of the Lusitana [sic] to attempt to retrieve documents and other valuables locked in her strongroom.

Cinema pictures and still photographs of the liner will be taken to show the world how the former pride of the Clyde lies shattered under the waves.

The venture is being organised by the Argonaut Corporation, Ltd., of London and Glasgow.

A ship named the Orphir is now being fitted out in the Beardmore Dockyard at Dalmuir.

The equipment embodies all the latest contributions of modern science and engineering to deep-sea exploration. One of the most valuable units is a flexible metal diving suit, fitted with mechanical hands, which will enable divers to work safely and comfortably in depths hitherto unattainable, with the mobility of the ordinary rubber dress.

Wonderfully, the (actually very fascinating) Coast Monkey website has some pictures of this state-of-the-art diving suit from 1935 being lowered into the water with intrepid diver Jim Jarrett inside, which you really need to see here to appreciate:

The metal dress was tested in Loch Ness by experts, who testified that at a depth of about 450 feet they had the same freedom of movement as was possible at only a few feet down.

With the new dress, divers will be able easily to reach the Lusitania, lying 280 feet deep, and work their way freely into the wreck, if necessary burning a passage through the steel hull with oxy-hydrogen burners.

Locating the Wreck

The article continues:

It is known that the Lusitania lies approximately ten miles off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland, and it will be necessary to scour about 15 square miles of the ocean bed to find her.

To eliminate the hit-or-miss element in the search, the organisers of the expedition will divide the area into squares, each of which will be explored in turn until the ship is located or the entire area covered.

A buoy will be anchored in the centre of the square, and measuring with a rangefinder the distance of the ship from the buoy, in conjunction with compass bearings, the invisible sea furrow ploughed by the ship will be accurately traced on a specially made chart. The chart will show the area covered each day, and make it impossible for the navigator to duplicate his tracks.

NOTHING FANTASTIC

Captain Henry Russell, marine superintendent of the expedition company, explained on Monday the method of operation in detail.

Captain Russell emphasised that there was nothing hare-brained or fantastic about the expedition. “I might emphasise that we are not going to make any attempt to refloat the Lusitania – a project which would be absurd,” he said.

“Nor do we expect to find any bullion on board. This is not a treasure-hunt. It is a practical demonstration of what can be done to explore the hitherto unrevealed secrets of the ocean bed with our modern apparatus.

“After the Lusitania we intend to explore other wrecks.”

Now, I can’t yet definitively prove that this Captain Henry Russell setting off to the Lusitania in 1935 with hi-tech sounding gear was the same Captain Russell who had previously gone to Mauritius on behalf of William Mansfield. But… I think it’s overwhelmingly likely.

His “Romantic Quest”

The Motherwell Times of 19th July 1935 (p.8) wasn’t fooled: this trip to the Lusitania was indeed “Captain Henry Russell’s Romantic Quest”:

Captain Henry Bell Russell, commander of the salvage vessel Orphir, which left Dalmuir on Monday afternoon on the first lap of her epic-making expedition, as a result of which it is hoped to raise the treasure of the Lusitania, the great Atlantic liner sunk off the Old Head of Kinsale on May 7, 1915, by a German U-Boat, is a Wishaw man.

His residence is in Coltness Road, Wishaw. Captain Russell has considerable experience of deep-sea diving work in the Persian Gulf as one of the masters employed by the Indo-Burma Petroleum Company, which has released him temporarily to command this unusual expedition.

So we now know that his full name was Henry Bell Russell, and that in 1935 he was living in Coltness Road, Wishaw. What do the archives have to tell us about this no-longer-unnamed man?

About Captain Henry Bell Russell

Thanks to the very useful ScotlandsPeople website, I was able to quickly find that:

- Henry Bell Russell was born in 1897 (in Govan, ref 646/2 1505)

- His first wife was Mary Eveline Arthur, they married in 1929 (in Kelvin, ref 644/13 246)

- Another Henry Bell Russell was born in 1933 (probably Captain Russell’s son?)

- Henry Bell Russell had a house and a cottage in Cardross in 1940

- His second wife was Mary Meehan Hamilton, they married in 1946 (Maryhill, ref 644/12/51)

- Henry Bell Russell died in 1989 (mother’s surname Imrie) aged 91 (Glasgow, ref 605/ 455)

Patrick O’Neil was able to confirm much of this (though via quite different databases):

- Henry Bell Russell was born 8th October 1897 in Govan

- His parents were Henry Russell, a commercial traveller born in 1869, and Margaret Russell, born 1871

- In the 1901 census, he had older sisters Margaret I (Imrie?) born 1896, Marion B (Bell?) born 1894, and Mary Mci (Macintosh?) born 1893.

- He joined the Navy on 12th December 1916 as a student: he became a quartermaster rating

- At that time, he was: 5 ft 4½ tall, 33 inch chest, black hair, blue eyes, fresh complexion.

- His first wife (according to the Shetland Times) was Mary Eveline “Queenie” Arthur, and they married on 2nd September 1929

- He later formed a metallurgy / chemistry company called United Compositions (Ltd), 108 Douglas Street, Glasgow, with Charles Norman Exley, a chemist of 16 Elie Street, Glasgow.

And, rather nicely, here’s a fetching picture of our fellow as a young man in his pre-Captain days:

I further found that from 1914 to 1916, he was enrolled at The Glasgow School of Art studying Drawing and Painting, leaving his course in December 1916 to sign up for the Navy. His address then was 9 Minerva Street in Glasgow.

Captain Russell’s Mysterious Second Wife

There’s one final scrap to throw to any genealogical wolves whose previous mild interest in Captain Russell hasn’t by now been utterly sated: a series of slightly confused posts from 2011 on GenesReunited by a poster called “Big” (whose account has since expired).

These relate to Captain Russell’s mysterious second wife Mary Meehan Hamilton: I additionally found a record of them travelling on the motor ship (MS) “Patella” from Curacao to New York in March 1947, which one might suspect was part of their honeymoon.

The poster “Big” seemed to think that Mary Meehan Hamilton was born in 1912, married a Mr Adams in 1924 (yes, really), had seven children (sadly some of whom died from diptheria), was with child when marrying Captain Russell, but married him bigamously under the surname “Cunningham” (her second husband’s surname).

Maybe inside all this morass of detail there’s a four-hour Snyder Cut of Captain Russell’s epic life just itching to be made, who knows?

And next…

Will there be a Part 4 to this story? Right now, I’m kind of hoping there won’t… but still, “never say never“, as they say in showbiz, amiright?