Here’s what I think the Voynich Wikipedia page ought to look like. Enjoy! 🙂

* * * * * * *

History of a Mystery

Once upon a time (in 1912) in a crumbling Jesuit college near Rome, an antiquarian bookseller called Wilfrid Voynich bought a mysterious enciphered handwritten book. Despite its length (240 pages) it was an ugly, badly-painted little thing, for sure: but its strange text and drawings caught his imagination — and that was that.

Once upon a time (in 1912) in a crumbling Jesuit college near Rome, an antiquarian bookseller called Wilfrid Voynich bought a mysterious enciphered handwritten book. Despite its length (240 pages) it was an ugly, badly-painted little thing, for sure: but its strange text and drawings caught his imagination — and that was that.

Having quickly convinced himself that it could only have been written by one particular smart-arse medieval monk by the name of Roger Bacon, Voynich then spent the rest of his life trying to persuade gullible and/or overspeculative academics to ‘prove’ that his hunch was right. All of which amounted to a waste of twenty years, because it hadn’t even slightly been written by Bacon. D’oh!

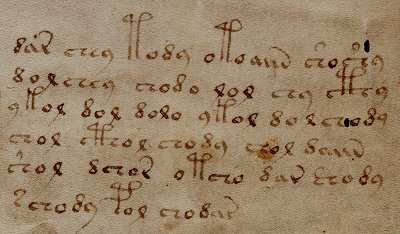

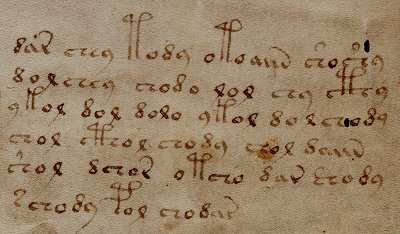

Oh, so you’d like to see some pictures of his ‘Voynich Manuscript’, would you? Well… go ahead, knock yourself out. First up, here’s some of its ‘Voynichese’ script, which people only tend to recognize if they had stopped taking their meds a few days previously:

Secondly, here’s one of the Voynich Manuscript’s many herbal drawings, almost all of which resemble mad scientist random hybrids of bits of other plants:-

Finally, here’s a close-up of one of its bizarre naked ladies (researchers call them ‘nymphs’, obviously trying not to mix business and pleasure), in this case apparently connected up to some odd-looking plumbing / tubing. Yup, the right word is indeed ‘bizarre’:

Did any of that help at all? No, probably not. So perhaps you can explain it now? No, I didn’t think so. Don’t worry, none of us can either. *sigh*

Back to the History Bit

Anyhow, tucked inside the manuscript was a letter dated 1665 from Johannes Marcus Marci in Prague, and addressed to the well-known delusional Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher. Marci’s letter said that he was giving the manuscript to Kircher both because of their friendship and because of Kircher’s reputation for being able to break any cipher. The manuscript seems then to have entered the Jesuit archives, which is presumably why the Jesuit college near Rome had it to sell to Wilfrid Voynich several centuries later, just as in all the best mystery novels.

But hold on a minute… might Wilfrid Voynich have forged his manuscript? Actually, a few years back researchers diligently dug up several other 17th century letters to Kircher almost certainly referring to the same thing, all of which makes the Voynich Manuscript at least 200 years older than Wilfrid Voynich. So no, he couldn’t have forged it, not without using Doc Brown’s flux capacitor. (Or possibly the time machine depicted in Quire 13. Unless that’s impossible.)

Incidentally, one of those other letters was from an obscure Prague alchemist called Georg Baresch, who seems to have wasted twenty or so years of his life pondering this curious object before giving it to Marci. So it would seem that twenty lost years is the de facto standard duration for Voynich research. Depressing, eh?

So, Where Did Baresch Get It From?

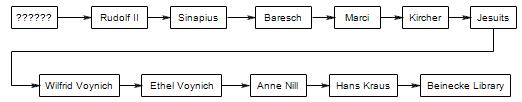

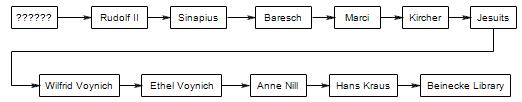

Well… Marci had heard it said that the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II had bought the manuscript for the ultra-tidy sum of 600 gold ducats, probably enough to buy a small castle. Similarly, Wilfrid Voynich discovered an erased signature for Sinapius (i.e. Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenecz, Rudolf II’s Imperial Distiller) on its front page. You can usefully assemble all these boring fragments of half-knowledge into a hugely unconvincing chain of ownership going all the way back to 1600-1610 or so, that would look something not entirely unlike this:-

Which is a bit of a shame, because in 2009 the Voynich Manuscript’s vellum was radiocarbon dated to 1404-1438 with 95% confidence. Hence it still has a gap of roughly 150 years on its reconstructed CV that we can’t account for at all – you know, the kind of hole that leads to those awkward pauses at job interviews, right before they shake your hand and say “We’ll let you know…”

Hence, The Real Question Is…

Fast-forward to 2012, and Wilfrid Voynich’s manuscript has ended up in New Haven at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Yet many Voynichologists seemed to have learnt little from all that has gone before, in that – just as with Wilfrid himself – they continue to waste decades of their life trying to prove that it is an [insert-theory-here] written by [insert-historical-figure-here].

If repeatedly pressed, such theorists tend to claim that:

* the ‘quest’ is everything;

* it is better to travel than to arrive; and even

* cracking the Voynich might somehow spoil its perfect inscrutability.

All of which, of course, makes no real sense to anyone but a Zen Master: but if their earnest wish is to remain armchair mountaineers with slippers for crampons, then so be it.

Yet ultimately, if you strip back the inevitable vanity and posturing, the only genuine question most people have at this point is:

How can I crack the Voynich Manuscript and become an eternal intellectual hero?

The answer is: unless you’re demonstrably a polymathic Intellectual History Renaissance Man or Woman with high-tensile steel cable for nerves, a supercomputer cluster the size of Peru for a brain, and who just happens to have read every book ever written on medieval/Renaissance history and examined every scratchy document in every archive, your chances are basically nil. Zero. Nada. Zilch. Honestly, it’s a blatant exaggeration but near enough to the truth true: so please try to get over it, OK?

Look, people have been analyzing the Voynich with computers since World War Two and still can’t reliably interpret a single letter – not a vowel, consonant, digit, punctuation mark, nothing. [A possible hyphen is about as good as it gets, honestly.] Nobody’s even sure if the spaces between words are genuinely spaces, if Voynichese ‘words’ are indeed actual words. *sigh*

Cryptologically, we can’t even properly tell what kind of an enciphering system was used – and if you can’t get that far, it should be no great surprise that applying massive computing power will yield no significant benefit. Basically, you can’t force your way into a castle with a battering ram if you don’t even know where its walls are. For the global community of clever-clogs codebreakers, can you even conceive of how embarrassing a failure this is, hmmm?

So, How Do We Crack It, Then?

If we do end up breaking the Voynich’s cipher, it looks unlikely that it will have been thanks to the superhuman efforts of a single Champollion-like person. Rather, it will most likely have come about from a succession of small things that get uncovered that all somehow cumulatively add up into some much bigger things. You could try to crack it yourself but… really, is there much sense in trying to climb Everest if everyone in the army of mountaineers that went before you has failed to work out even where base camp should go? It’s not hugely clear that even half of them even were looking at the right mountain.

All the same, there are dozens of open questions ranging across a wide set of fields (e.g. codicology, palaeography, statistical analysis, cryptanalysis, etc), each of which might help to move our collective understanding of the Voynich Manuscript forward if we could only answer them. For example…

* Can we find a handwriting match for the marginalia? [More details here & here]

* Can we find a reliable way of reading the wonky marginalia (particularly on f116v, the endmost page)? [More details here]

* Can we find another document using the same unusual quire numbering scheme (‘abbreviated longhand Roman ordinals’)? [More details here].

* Precisely how do state machine models of the Voynich’s two ‘Currier language’s differ? Moreover, why do they differ? [More details here]

* etc

The basic idea here is that if you can’t do big at all, do us all a favour and try to do small well instead. But nobody’s listening: and so it all goes on, year after year. What a waste of time. 🙁

A Warning From History

Finally: I completely understand that you’re a busy person with lots on your mind, so the chances are you’ll forget almost all of the above within a matter of minutes. Possibly even seconds. And that’s OK. But if you can only spare sufficient mental capacity to remember a seven-word soundbite from this whole dismal summary, perhaps they ought to be:

Underestimate the Voynich Manuscript at your peril!

Now ain’t that the truth!?

Once upon a time (in 1912) in a crumbling Jesuit college near Rome, an antiquarian bookseller called Wilfrid Voynich bought a mysterious enciphered handwritten book. Despite its length (240 pages) it was an ugly, badly-painted little thing, for sure: but its strange text and drawings caught his imagination — and that was that.

Once upon a time (in 1912) in a crumbling Jesuit college near Rome, an antiquarian bookseller called Wilfrid Voynich bought a mysterious enciphered handwritten book. Despite its length (240 pages) it was an ugly, badly-painted little thing, for sure: but its strange text and drawings caught his imagination — and that was that.