Who was the mysterious French sea captain who Le Butin (Bernardin Nageon de L’estang) got his pirate cipher from?

Le Butin claimed that this captain was mortally wounded in a naval battle with “a large British frigate on the shores of Hindoustan”, and on his deathbed – and having confirmed that Le Butin was a Freemason – he passed Le Butin his pirate treasure secrets, now widely presumed to be La Buse’s pigpen cryptogram.

All in all, taking this at face gives us a pretty specific historical puzzle to solve – we know where it happened (off the coast of Hindustan, so not too far from the ports of Surat, Diu, and Daman), broadly who did it (a large English frigate), and broadly when it happened (sometime in the 1790s). But can we be more specific?

Trying a little too hard for a quick answer, I drew up a list of Indian Ocean French corsairs who died during that period (perhaps surprisingly, many of them seemed to live to a tidy old age – crime may not pay, but state-licensed crime apparently does). For example, the French corsair Claude Deschiens de Kerulvay died on 11th September 1796 on his ship the Modeste having been wounded in a sea-battle with two well-armed English whalers the previous day… but that was off the coast of Mozambique. So, no real match there, it would seem. And the same proved to be the case with just about all the others.

I also previously dug up a mention of a sea battle of the coast of Hindustan that happened on 9th February 1796, where three French warships sailing under false flags engaged with the coastguard ship Real Fidelissima just off Diu. But that was a small Portuguese ship, guarding a Portuguese port in India… once again, “close, but no cigar”.

Even so, I worked out that two of the three French warships that attacked Diu were almost certainly the Cybèle (under Captain Renaud) and the Prudente (under Captain Tréhouart). The third ship might have been the brig Coureur (under Lieutenant Garaud), the corvette Pélagie (under Lieutenant Latour-Cassanhiol) which had joined Renaud’s division in 1795, the Jean-Bart (formerly the Rosalie, under Captain Loyseau), or even Deschiens de Kerulvay’s Modeste. Incidentally, the Modeste was laid up in May 1796, which would be broadly consistent with its having been the ship that the Portuguese coastguard and fort cannons damaged in the action off Diu… but that’s a bit thin as inferences go.

I think we can be a little more specific about the timing, though. Specifically, it seems very unlikely to me that it would have been after the summer of 1796, when the truly formidable Admiral de Sercey (who is commemorated on the Arc de Triomphe!) took control of the French Mauritius fleet. And given that the number of attacks by French corsairs on the British East India ships ballooned after 1793, the date range we’re interested in is probably from late 1793 to July 1796. That’s a reasonably good start… but not quite good enough. And so it was there that my train ran out of steam.

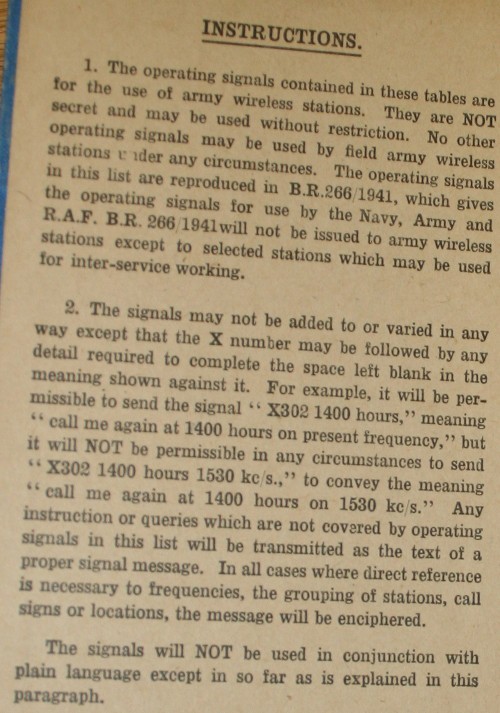

But then a copy of H.C.M. Austen’s (1934) “Sea Fights and Corsairs of the Indian Ocean” arrived through the post (the Cipher Mysteries budget only stretched to the 2003 paperback 2nd edition, but even that was hard enough to find). Having this lovely old slab to hand allowed me to cross-reference everything I’d found so far with Austen’s detailed accounts of the various Indian Ocean naval actions [even if some parts of it have clearly been superseded by modern research].

Even though I’m only half-way through it (it’s a big old thing, really it is), I’m now pretty sure that Le Butin’s dying captain will turn out to be none other than Jean-Marie Renaud, head of the French Navy’s Indian Station.

Renaud’s main claim to naval fame came from the action of 22nd October 1794, when he proposed a way to break the British blockade of Mauritius’ Port Louis. The Cybèle and the Prudente were badly damaged in the sea fight (and Renaud himself was wounded, though not fatally), but Renaud’s plan worked, and the blockade was lifted… for a few weeks, anyway.

Austen continues (p.64)…

Early in 1795, as soon as the two frigates had been repaired, Renaud took them out as naval corsairs. On 30th June, in the Straits of Sunda, they captured the Sea Nymph; on 8th July, in the mouth of the Palimban River, a Dutch and many other ships, one of which, the Acheines of 400 tons, was ransomed by the Nabob of Arcot for 120,000 francs.

…before finishing with a sentence that is both mysterious and unsatisfying…

No historian has as yet been able to trace the ultimate fate of Renaud.

The the Wikipedia page on Renaud asserts that (and:-

* “capitaine de vaisseau Renaud” was in Guyane in 1799 [BB4 139. CAMPAGNES. 1799. VOLUME 10]

* “capitaine Renaud”, captaining the Frigate Syrène in 1801 as per this quote from Guerin’s “Histoire maritime de France” (p.211) [note that “Cayenne” was the French colony in Guyana]:-

“La corvette le Berceau remplaçait, dans la station de Cayenne, la frégate la Syrène, capitaine Renaud, qui, après un beau combat contre deux frégates anglaises, était allée déposer dans cette colonie le commissaire Victor Hugues, et elle avait en levé, le 10 juillet 1800, une bonne partie d’un convoi anglo-por tugais, amariné une corvette et mis en fuite un brig d’escorte, lorsque ayant conduit à bon port ses prises évaluées à plus de quatre millions, elle fut rencontrée par la frégate le Boston, de 32 canons, avec laquelle il lui fallut soutenir trois combats successifs à portée de pistolet.“

I also found one further possible Renaud reference listed in the French Marine archives:

* “cdt. Renaud, enseigne de vaisseau” was commanding a ship called the Unité full of prisoners between Toulon and Mahon in 1801 [BB4 156. CAMPAGNES. 1801. VOLUME 6]

But no, I don’t believe that any of these references are to the same M. Renaud who sailed the Indian Ocean. For a start, I don’t believe that Renaud ever returned to France – the hero of the 1794 naval action would surely have merited some kind of official response, whether a pension or an honour. And for another, I simply don’t believe that he would have gone completely silent for 3-4 years at what was essentially the peak of his career.

No, the French marine archives of the period are sufficiently detailed and complete that any move by a well-thought-of figure would have been carefully noted (particularly by the enthusiastically bureaucratic Admiral de Sercey, whose letters fill the French Marine archives), but honestly, there’s nowt t’see there. OK, you may say that “absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence”: but here we do have plenty of evidence in the archives, all saying nothing about what Renaud was doing. To me, that’s arguably as close to “evidence of absence” as you’re likely to get.

I’d agree that a man about whose family, birth (place and date) and death (place and date) we currently know nothing is always going to be an easy lapel to pin a mystery medal on. But if I’ve got him figured out right, what’s the next step, hmmm?

Well… so far, I’ve played most of this from the French archival side: but now it’s time to (you’re way ahead of me) jump ship over to the British archives.

Hence my plan (such as it is) is to try to work out what large British frigates were anywhere near the Hindustan coast between 9th February 1796 (when Diu was attacked) and late March 1796 (when Captain Galloway of the American ship Restoration said “the Prudente, the Cybèle and a corvette returned to Port Louis … without any prizes.“). It’s a pretty tight window.

Really, the list of possible British ships who were in the exact place at the exact time must surely be quite short (no more than three or four?), so finding those out should be relatively straightforward. The carrot on the stick is that the papers of many British ships of this period are still accessible, along with contemporary Admiralty reports etc: so once those ship names are in hand, I believe it should be possible to go straight to the primary evidence and see what it tells us. There may be quite an unexpected story to be found there, you never know… 🙂

PS: there may possibly be more to see in BB4 86. CAMPAGNES. 1795. VOLUME 23 in the French Marine archives, as I’ve only seen the item summary: “Frégate la Prudente (croisière autour de Sumatra ; Saint-Denis-de-la-Réunion), cdt. Renaud, capitaine de vaisseau à titre temporaire. 2 frim. an IV” (i.e. cruising around Sumatra, 23rd November 1795). Even so, I suspect that’s where Renaud goes off the French radar and possibly onto the British radar… hopefully we shall see!