Here’s something I stumbled upon recently: a Victorian code world of gloves, handkerchiefs, hats, eyes, parasols and even stamps. Basically, the 1890s saw a craze for flirtation codes, using everyday objects close at hand to signal your romantic intentions and responses. I particularly like the specificity of “I will be at the gate at 8 p.m.”, but I guess that’s just me. 🙂

There were numerous variations of these: usefully, an 1891 edition of the Taranaki Herald (New Plymouth New Zealand) lists several such codes, which I have transcribed below:-

GLOVE FLIRTATION.Holding with tips downward - I wish to be acquainted.

Twirling around the fingers - Be careful! We are watched.

Right hand with the naked thumb exposed - Kiss me.

Left hand with the naked thumb exposed - Do you love me?

Using them as fan - Introduce me to your company.

Smoothing them out gently - I wish I were with you.

Holding them loose in the left hand - Be contented.

Biting the tips - I wish to be rid of you very soon.

Folding up carefully - Get rid of your company.

Striking them over the hand - I am displeased.

Drawing half way on left hand - Indifference.

Clenching them (rolled up) in right hand - No.

Striking over the shoulder - Follow me.

Ends of tips to lips - Do you love me?

Tossing them up gently - I am engaged.

Turning them inside out - I hate you.

Dropping both of them - I love you.

Tapping the chin - I love another.

Putting them away - I'm vexed.

Dropping one of them - Yes.HANDKERCHIEF FLIRTATION.

Drawing across the lips - Desirous of an acquaintance.

Drawing across the eyes - I am sorry.

Taking it by the centre - You are willing.

Dropping - We will be friends!

Twirling in both hands - Indifference.

Drawing across the cheek - I love you.

Drawing through the hands - I hate you.

Letting it rest on the right cheek - Yes.

Letting it rest on the left cheek - No.

Twisting in the left hand - I wish to be rid of you.

Twisting in the right hand - I love another.

Folding it - I wish to speak with you.

Over the shoulder - Follow me.

Opposite corners in both hands - Wait for me.

Drawing across the forehead - We are watched.

Placing on the right ear - You have changed.

Letting it remain on the eyes - You are cruel.

Winding around the forefinger - I am engaged.

Winding around the third finger - I am married.

Putting in the pocket - No more at present.PARASOL FLIRTATION.

Carrying it elevated in left hand - Desiring acquaintance.

Carrying elevated in right hand - You're too willing.

Carrying closed in left hand, by side - Follow me.

Carrying in front of you - No more at present.

Carrying over shoulder - You are too cruel.

Closing it up - I wish to speak with you.

Dropping it - I love you.

Folding it up - Get rid of your company.

Letting it rest on the left cheek - No.

Letting it rest on the right cheek - Yes.

Striking on hand - I am much displeased.

Swinging it to and fro by the handle on the right side - I am married.

Swinging same on left side - I am engaged.

Tapping the chin - I am in love with another.

Twirling it around - We are watched.

Using as a fan - Introduce me to your company.

With handle to lips - Kiss me.

Putting away - No more at present.FAN FLIRTATION.

Carrying right hand in front of face - Follow me.

Carrying in left hand - Desirous of an acquaintance.

Placing it on the right ear - You have changed.

Twirling it in left hand - I wish to get rid of you.

Drawing across forehead - We are watched.

Carrying in right hand - You are too willing.

Drawing through the hand - I hate you.

Twirling in right hand - I love another.

Drawing across the cheek - I love you.

Closing it - I wish to speak to you.

Drawing across the eye - I am sorry.

Letting it rest on right cheek - Yes.

Letting it rest on left cheek - No.

Open and shut - You are cruel.

Dropping - We will be friends.

Fanning slow - I am married.

Fanning fast - I am engaged.

With handle to lips - Kiss me.

Shut - You have changed.

Open wide - Wait for me.HAT FLIRTATION.

Carrying it in the right hand - Desirous of an acquaintance.

Carrying it in the left hand - I hate you!

Running the finger around the crown - I love you.

Running the hand around the rim - I hate you.

To wear on the right side of the head - No.

To wear on the left side of the head - Yes.

To wear on the back of the head — I wish to speak with you.

To incline towards the nose — We are watched.

Putting it behind you — I am married.

Putting it in front of you — I am single.

Carrying in the band by the crown — Follow me.

Putting it under the right arm — Wait for me.

Putting it under the left arm — I will be at the gate at 8 p.m.

Putting the hat on the head straight — All for the present.EYE FLIRTATION.

Winking the right eye - I love you.

Winking the left eye - I hate you.

Winking both eyes - Yes.

Winking both eyes at once - We are watched.

Winking right eye twice - I am engaged.

Winking left eye twice - I am married.

Dropping the eyelids - May I kiss you?

Raising the eyebrows - Kiss me.

Closing the left eye slowly - Try and love me.

Closing the right eye slowly - You are beautiful.

Placing right forefinger to right eye - Do you love me?

Placing right forefinger to left eye - You are handsome.

Placing right little finger to the right eye - Aren't you ashamed?

All of which is a lot like all the foolishly faked-up floriography that Victorians loved so much: but why say it with flowers when you can say it with a fan?

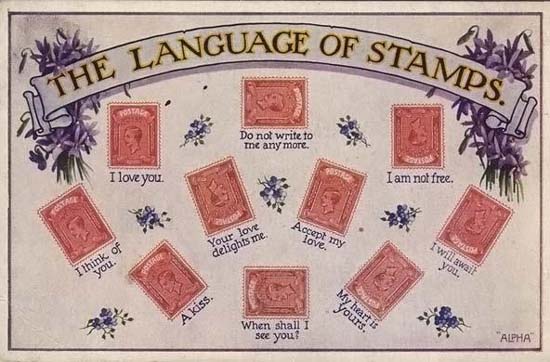

Anyway, I have to say that these promenading picayunes pale into paltriness compared with something else I found in the same web-trawling session: the (frankly astonishing) secret world of stamp codes.

You’ve already guessed when these flourished (same as above), what they said (same as above) and how they worked (same as above): all I can add is that here’s a link to a truly epic webpage devoted to a whole variety of stamp codes, highly recommended. Fabulous stuff… enjoy! 🙂