About a month ago, I mentioned here that there was an upcoming episode of “Ihr Auftrag, Pater Castell” with a Voynich theme. Well… this aired on ZDF on 5th November 2009, and (with a tip of the hat to Michael Johne’s voynichlupe blog) here’s a link to the “Das Voynich-Manuskript” episode online so that you can watch it yourself.

It’s one of those programmes where the main characters are pretty much so well-defined that you don’t actually need to understand German to make sense of what’s going on. The only bit that I didn’t quite get is how Pater Castell used the page from the book from the school library to decipher the note on the noticeboard (yes, Charles, it does sound like a text adventure).

Having gone to a boy’s school myself (though since it went fully co-ed, Brentwood’s most famous ‘old boy’ is now Jodie Marsh, horror of horrors), I have to say that the most implausible bit of the episode was the way that the sexy Münchner detective Marie Blank walked around the school in tight white jeans without any of the sixth formers giving her a second look. Oh well… artistic licence, I s’pose.

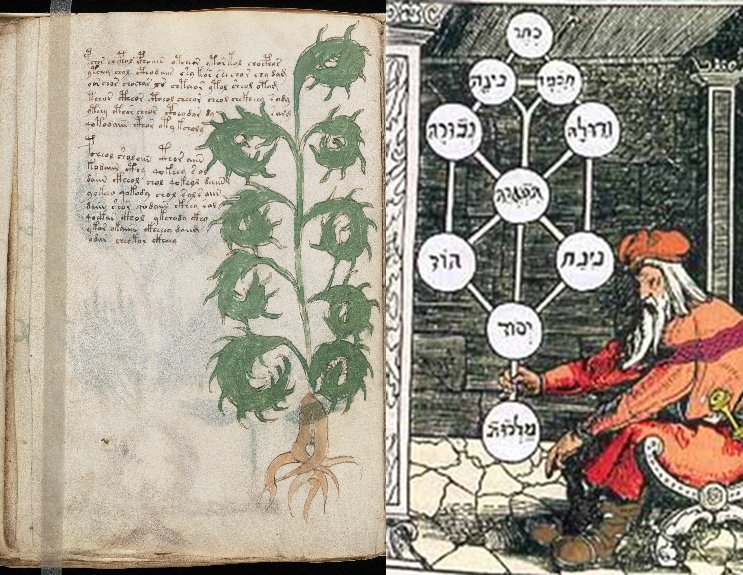

For maximum Voynich spotter points, have your copy of “Le Code Voynich” open to page f52v, and observe the nine vaguely fern-ish leaf-swirls rolling over as they branch off a single vertical stem – though quite why Pater Castell mumbles “Kabbalah” to himself as he looks at this page is a little beyond me (sorry, but to my eyes it doesn’t resemble the Ten Sephiroth at all). For what it’s worth (typically £9.95 + p&p), I suspect that this page is a late “A” page, and was part of the Voynich author’s transitional phase which used the ‘A’ language and fake plants to represent other things – in this case, a fountain.

One question that bugged me throughout the episode was… whom exactly did the main character remind me of? It took me right until the end to work out the alchemical wedding from whence Pater Castell (played by Francis Fulton-Smith) seems to have sprung…

Yes, he’s the offspring of Steven Seagal and Dom Joly. Watch it for yourself and see if you agree.

And finally: structurally, “Ihr Auftrag, Pater Castell” reminded me of another well-known TV series which combines two strong main characters’ arbitrarily flying around in a light aircraft with blocky expositions of things that are mysteries to its (admittedly slightly younger) viewers, all sweetened by a bit of light drama. I’m referring, of course, to “Come Outside” (1994), featuring Lynda Baron (as Aunt Mabel) and her clever dog Pippin – a far more rounded role than her appearances on Eastenders as Jane Beale’s mum. (Though I d-d-doubt Arkwright would accuse Nurse Gladys Emanuel of being anything but fully rounded.)

For reference, Pippin’s the one without the goggles. Actually, “Come Outside” is a sweet little series for kids, and I hope it continues to be shown until at least the year 2999. 🙂