Though the Dean at All Saints in the Citadel of Prague was one of the earliest people to mention the Voynich Manuscript (in two letters to his old friend Athanasius Kircher), poor old Godefridus (Gottfried) Aloysius Kinner of Löwenthurn hasn’t really featured much in the discussion so far.

In Kinner’s letter dated 4th January 1666, he mentions to Kircher that their mutual friend Johannes Marcus Marci asked after “that arcane book which he gave up to you“, which itself seems to mark Marci’s (rather more famous) letter to Kircher as genuine. Kinner also expresses cynicism about alchemy, judging it to be as “worthless” as judicial astrology has proved to be.

Kinner’s letter dated 5 January 1667 from the following New Year finds him still battling with asthma and a cough, and notes that even though Marci “has lost his memory of nearly everything“, he still “wishes to know through me whether you have yet proved an Oedipus in solving that book which he sent via the Father Provincial last year and what mysteries you think it may contain“. He also laments the recent death of Gasparus Schott.

Up until now, most Voynich-related archival search has been carried out by relentlessly trawling through Kircher’s obsessively overflowing (and increasingly well-documented and accessible) inbox. However, for all its interest, this is rather like hearing only one side of a phone conversation – there’s only so much you can reliably infer. I wondered: might there be other letters from/to Kinner out there, or perhaps even books (as these often contained copies of letters)?

A quick online trawl turned up some Kinner letters from 1664-1665 with Christiaan Huygens, reproduced in book V of his “Œuvres complètes”. Curiously, Huygens’ correspondence was published in 22 volumes (from 1888-1950!) yet doesn’t seem to get mentioned much (I ought to add it to my list of correspondence projects): presumably we’d be most interested in looking at “Tome Sixieme: Correspondance 1666-1669” (which I don’t think is online)…

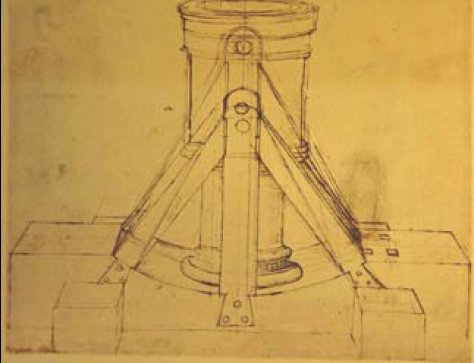

The mention of the Jesuit Gaspar Schott in Kinner’s 1667 letter is also interesting: not only did Schott study under Kircher, he also (while a Professor at Palermo) corresponded with Guericke, Huygens and Boyle, compiling it all into the “Organum mathematicum“, a massive collection of novelties and things of contemporary interest… which Kinner helped edit. Such are the bonds which tie a community together.

Incidentally, the nine volumes of the Organum are: (1) Arithmeticus, (2) Geometricus, (3) Fortificatorius, (4) Chronologicus, (5) Horographicus, (6) Astronomicus, (7) Astrologicus, (8) Steganographicus, (9) Musicus. Of course, book eight might be the most interesting for Voynich researchers. 🙂

WorldCat lists other books by Kinner, such as his (1653) “Elucidatio geometrica problematis austriaci sive quadraturæ circuli“, and his (1664) “Stella Matutina In Medio Nebulae, Sive Laudatio Funebris“, but I somehow doubt that these will produce anything useful.

From all the above, it should be clear here that we are talking about an active community of people continually corresponding across Europe: and indeed, over recent decades letters have become perhaps the most fashionable form of historical documentation amongst early modern / Renaissance historians.

So, you would have thought it would be useful to find out if there is an archive somewhere that just happens to have more correspondence from Kinner, right?

However sensible an idea, this immediately runs into a brick wall: the lack of any kind of cross-collection finding aid for early modern historical correspondence. In fact, libraries’ and private collections’ programmes for scanning and indexing letters are decades behind the many (far more high-visibility) book-scanning programmes. Funding-wise, it seems that books are “sexy”, while letters are “unsexy”: but actually, ask working historians and you’ll find that this is just wrong.

My guess is that the right place to start such a quest would be Book VI of Huygens’ Oeuvres Complètes, to see if it says where Huygens’ correspondence to/from Kinner is held. It may well be that this points the way to more of the same, who knows?

UPDATE: thanks to Christopher Hagedorn’s exemplary persistence in the face of the BnF’s flaky servers, we now have a direct link to Book VI of Huygens’ Oeuvres Complètes. From this we can tell that Kinner’s correspondence seems to stop dead in 1667, the same year that Marci died. My guess is that perhaps this too marked the end of Kinner’s life (and the likely end of this avenue). Ah well. 🙁