Artist Anna-Lise Horsley has a mini online art gallery of her work on the Saatchi Online gallery: inspired by all kinds of floral and herbal shapes and shadows, two works showcased are “Spode Voynich” and “Voynich Poppy” (both from 2008). I’d have to say that I prefer her “Pandemonium” (2009), but each to their own, eh? As to what they mean, I can only say: “annalise this“! 🙂

At the start of my own VMs research path, I thought it was important to consider everyone’s observations and interpretations (however, errrm, ‘fruity’) as each one may just possibly contain that single mythical seed of truth which could be nurtured and grown into a substantial tree of knowledge. Sadly, however, it has become progressively clearer to me as time has passed that any resemblance between most Voynich researchers’ interpretations (i.e. not you, dear reader) and what the VMs actually contains is likely to be purely coincidental.

Why is this so? It’s not because Voynich researchers are any less perceptive or any more credulous than ‘mainstream’ historians (who are indeed just as able to make fools of themselves when the evidence gets murky, as Voynich evidence most certainly is). Rather, I think it is because there are some ghosts in our path – illusory notions that mislead and hinder us as we try to move forward.

So: in a brave (but probably futile) bid to exorcise these haunted souls, here is my field guide to what I consider the four main ghosts who gently steer people off the (already difficult) road into the vast tracts of quagmire just beside it…

Ghost #1: “the marginalia must be enciphered, and so it is a waste of time to try to read them”

I’ve heard this from plenty of people, and recently even from a top-tier palaeographer (though it wasn’t David Ganz, if you’re asking). I’d fully agree that…

- The Voynich Manuscript’s marginalia are in a mess

- To be precise, they are in a near-unreadable state

- They appear to be composed of fragments of different languages

- There’s not a lot of them to work with, yet…

- There is a high chance that these were written by the author or by someone remarkably close to the author’s project

As with most non-trick coins, there are two quite different sides you can spin all this: either as (a) good reasons to run away at high speed, or as (b) heralds calling us to great adventure. But all the same, running away should be for properly rational reasons: whereas simply dismissing the marginalia as fragments of an eternally-unreadable ciphertext seems to be simply an alibi for not rising to their challenge – there seems (the smattering of Voynichese embedded in them aside) no good reason to think that this is written in cipher.

Furthermore, the awkward question here is that given that the VMs’ author was able to construct such a sophisticated cipher alphabet and sustain it over several hundred pages in clearly readable text, why add a quite different (but hugely obscure) one on the back page in such unreadable text?

(My preferred explanation is that later owners emended the marginalia to try to salvage its (already noticeably faded) text: but for all their good intentions, they left it in a worse mess than the one they inherited. And this is a hypothesis that can be tested directly with multispectral and/or Raman scanning.)

Ghost #2: “the current page order was the original page order, or at least was the direct intention of the original author”

As evidence for this, you could point out that the quire numbers and folio numbers are basically in order, and that pretty much all the obvious paint transfers between pages occurred in the present binding order (i.e. the gathering and nesting order): so why should the bifolio order be wrong?

Actually, there are several good reasons: for one, Q13 (“Quire 13”) has a drawing that was originally rendered across the central fold of a bifolio as an inside bifolio. Also, a few long downstrokes on some early Herbal quires reappear in the wrong quire completely. And the (presumably later) rebinding of Q9 has made the quire numbering subtly inconsistent with the folio numbering. Also, the way that Herbal A and Herbal B pages are mixed up, and the way that the handwriting on adjacent pages often changes styles dramatically would seem to indicate some kind of scrambling has taken place right through the herbal quires. Finally, it seems highly likely that the original second innermost bifolio on Q13 was Q13’s current outer bifolio (but inside out!), which would imply that at least some bifolio scrambling took place even before the quire numbers were added.

Yet some smart people (most notably Glen Claston) continue to argue that this ghost is a reality: and why would GC be wrong about this when he is so meticulous about other things? I suspect that the silent partner to his argument here is Leonell Strong’s claimed decipherment: and that some aspect of that decipherment requires that the page order we now see can only be the original. It, of course, would be wonderful if this were true: but given that I remain unconvinced that Strong’s “(0)135797531474” offset key is correct (or even historically plausible for the mid-15th century, particularly when combined with a putative set of orthographic rules that the encipherer is deemed to be trying to follow), I have yet to accept this as de facto codicological evidence.

To be fair, GC now asserts that the original author consciously reordered the pages according to some unknown guiding principle, deliberately reversing bifolios, swapping them round and inserting extra bifolios so that their content would follow some organizational plan we currently have no real idea about. Though this is a pretty sophisticated attempt at a save, I’m just not convinced: I’m pretty sure (for example) that Q9 and the pharma quires were rebound for handling convenience – in Q9’s case, this involved rebinding it along a different fold to make it less lopsided, while in the pharma quires’ case, I suspect that all the wide bifolios from the herbal section were simply stitched together for convenience.

Ghost #3: “Voynichese is a single language that remained static during the writing process”

If you stand at the foot of a cliff and de-focus your gaze to take in the whole vertical face in one go, you’d never be able to climb it: you’d be overawed by the entire vast assembly. No: the way to make such an ascent is to strategize an overall approach and tackle it one hand- and foot-hold at a time. Similarly, I think many Voynich researchers seem to stand agog at the vastness of the overall ciphertext challenge they face: whereas in fact, with the right set of ideas (and a good methodology) it should really be possible to crack it one page (or one paragraph, line, word, or perhaps even letter) at a time.

Yet the problem is that many researchers rely on aggregating statistics calculated over the entire manuscript, when common sense shows that different parts have very different profiles – not just Currier A and Currier B, but also labels, radial lines, circular fragments, etc. I also think it extraordinarily likely that a number of “space insertion ciphers” have been used in various places to break up long words and repeating patterns (both of which are key cryptographic tells). Therefore, I would caution all Voynich researchers relying on statistical evidence for their observations that they should be extremely careful about selecting pragmatic subsets of the VMs when trying to draw conclusions.

Happily, some people (most notably Marke Fincher and Rene Zandbergen) have come round to the idea that the Voynichese system evolved over the course of the writing process – but even they don’t yet seem comfortable with taking this idea right to its limit. Which is this: that if we properly understood the dynamics by which the Voynichese system evolved, we would be able to re-sequence the pages into their original order of construction (which should be hugely revealing in its own right), and then start to reach towards an understanding of the reasons for that evolution – specfically, what type of cipher “tells” the author was trying to avoid presenting.

For example: “early” pages neither have word-initial “l-” nor do we see the word “qol” appear, yet this is very common later. If we compare the Markov states for early and late pages, could we identify what early-page structure that late-page “l-” is standing in for? If we can do this, then I think we would get a very different perspective on the stats – and on the nature of the ‘language’ itself. And similarly for other tokens such as “cXh” (strikethrough gallows), etc.

Ghost #4: “the text and paints we see have remained essentially unchanged over time”

It is easy to just take the entire artefact as a fait accompli – something presented to our modern eyes as a perfect expression of an unknown intention (this is usually supported by arguments about the apparently low number of corrections). If you do, the trap you can then fall headlong in is to try to rationalize every feature as deliberate. But is that necessarily so?

Jorge Stolfi has pointed out a number of places where it looks as though corrections and emendations have been made, both to the text and to the drawings, with perhaps the most notorious “layerer” of all being his putative “heavy painter” – someone who appears to have come in at a late stage (say, late 16th century) to beautify the mostly-unadorned drawings with a fairly slapdash paint job.

Many pages also make me wonder about the assumption of perfection, and possibly none more so than f55r. This is the herbal page with the red lead lines still in the flowers which I gently parodied here: it is also (unusually) has two EVA ‘x’ characters on line 8. There’s also an unusual word-terminal “-ai” on line 10 (qokar or arai o ar odaiiin) [one of only three in the VMs?], a standalone “dl” word on line 12 [sure, dl appears 70+ times, but it still looks odd to me], and a good number of ambiguous o/a characters. To my eye, there’s something unfinished and imperfectly corrected about both the text and the pictures here that I can’t shake off, as if the author had fallen ill while composing it, and tidied it up in a state of distress or discomfort: it just doesn’t feel as slick as most pages.

I have also had a stab at assessing likely error rates in the VMs (though I can’t now find the post, must have noted it down wrong) and concluded that the VMs is, just as Tony Gaffney points out with printed ciphers, probably riddled with copying errors.

No: unlike Paul McCartney’s portable Buddha statue, the Voynich Manuscript’s inscrutability neither implies inner perfection nor gives us a glimmer of peace. Rather, it shouts “Mu!” and forces us to microscopically focus on its imperfections so that we can move past its numerous paradoxes – all of which arguably makes the VMs the biggest koan ever constructed. Just so you know! 🙂

You may well have heard of the furore surrounding King’s College London’s recent decision to get rid of roughly 10% of its academic staff, including (perhaps most controversially) its Chair of Palaeography, currently held by David Ganz. I’ve been trying for months to raise a big enough head of Daily Mail-esque columnist steam to vent some anger about this downsizing… but I just can’t do it. I’m angry, but probably not for the reasons you might expect.

If Kings were instead talking about getting rid of a Chair of Etymology (perhaps sponsored by the authors of all those annoying books about banal words that seem to have taken over bookshop tills?), a Chair of Phrenology, or indeed a chair in any other of those useless Victorian sub-steam-punk nonsensical technical subjects, nobody would bat an eyelid. All the same, palaeography is arguably an exception because raw historical text is almost a magical thing: ideas written down have a slow life far beyond that of their author’s, making palaeography the art of keeping written ideas alive.

Yet one of the things muddying the waters here is that there are two quite distinct palaeographies at play: firstly, there’s the classic Victorian handwriting collectoriana side of Palaeography, by which vast collections of hands were amassed and (as I understand it) spuriously positivistic developmental trees constructed; while secondly, there is a modern technical, forensic side to the subject more to do with ductus, and closely allied with codicology. What the two sides share is that practitioners are good at reading stuff, and like to help people to read stuff they want to. Yet to my eyes, the dirty little secret is that the ductus / forensic side of the subject is rarely integrated with the craft knowledge / practitioner side of the subject.

Yet historians will always need to read texts: and the number of manuscripts scanned and available on the web must be at least doubling each year. So at a time when accessible texts are proliferating, why is palaeography itself in decline?

For me, the root problem lies in history itself. When I was at school, History was taught as The Grand Accumulation Of Facts About Grand Men In History (which, though a nonsensical approach, was at least a long-standing nonsensical approach): while nowadays, the ascendancy of Burkeian social history has turned vast swathes of the subject instead into a wayward empathy fest – Feeling How It Felt To Feel Like An Unprivileged Pleb Just Like You (but without a plasma screen and iPhone) In The Very Olden Days. No less nonsensical, no less useless.

Actually, my firm belief is that taught History should not be a recital of that-which-has-happened, but should instead be the process of teaching people of all ages how to find out what happened in the past for themselves. When I look at contemporary events and documents (dodgy dossiers, Dr David Kelly, Jean Charles de Menezes, etc), I interpret our shabby public response as a collective failure of history teaching. We are not taught how to think critically about documentary evidence, even though this is a skill utterly central to active citizenship.

And so I think History-as-taught-at-schools should be about primary evidence, about reliability of sources, about practising exercising judgment. Really, I think it should start neither with Kings & Queens nor with plebs, but instead with codicology and palaeography: if you believe in the primacy of evidence, then you should teach that as the starting point. It’s everything else about history that is basically bunk!

Personally, I would re-label codicology as “material forensics” and palaeography as “textual forensics” (I’m not sure how serious people are about wanting to rename the latter ‘diachronic decoding’, but that’s almost too ghastly a Dan-Brown-ism to consider), and would build the first year of historical curricula in schools around the nature and limits of Evidence – basically, the epistemology of pragmatic history. To me, the fact that palaeography only kicks in as a postgraduate module is what we should be ashamed of.

So, who signed Palaeography’s death warrant? Not King’s College’s vastly overpaid administrators, then, but instead all those historians who have chosen not only to back away from primary evidence but also to teach others to do the same. David Ganz should be teaching school teachers how to inspire children around evidence: and it is our own fault that palaeography has become so stupidly marginalized in mainstream historical practice that the King’s College administrators’ desire to get rid of it can seem so reasonable.

Trying to pin blame on King’s College is, I would say, missing the point: which is that we collectively killed palaeography already. If the overall project was to get rid of romantic, delusional, denialist History (and much social history as practised has just as romantic a central narrative thread as the Big Man history it aimed to supplant), fair enough: but rather than leave a conceptual vacuum in its wake, it should be replaced with skeptical, pragmatic History (based on solid forensic thinking and an appreciation of the internal agendas behind texts). I believe that this would yield good critical thinking skills as well as exactly the kind of good citizenship politicians so often say is missing.

But… what are the chances of that, eh?

I used to quite like Peanuts as a kid, though looking back I’d be hard-pressed to say which of the characters I particularly identified with. Perhaps identifying with characters is more of an adult way of relating to cultural objets d’art: I think I just liked the jokes.

Of course, nothing in the following badly-hacked Peanuts cartoon is anything to do with you, you understand, dear Cipher Mysteries reader: as with the hacked Garfield-does-Voynich strip, it’s just a bunch of asemic words arranged in speech bubbles beside someone else’s copyrighted images. So feel completely free to make of it precisely what you will. Enjoy!

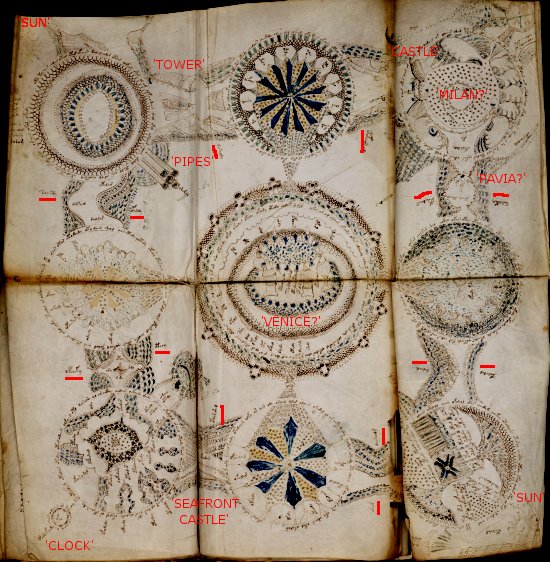

For the most part, constructing plausible explanations for the drawings in the Voynich Manuscript is a fairly straightforward exercise. Even its apparently-weird botany could well be subtly rational (for example, if plants on opposite pages swapped their roots over in the original binding, in a kind of visual anagram), as could the astronomy, the astrology, and the water / balneology quires (if all perhaps somewhat obfuscated). Yet this house of oh-so-sensible cards gets blown away by the hurricane of oddness that is the Voynich Manuscript’s nine-rosette page.

If you’re not intrigued by this, you really do have a heart of granite, because of all the VMs’ pages, this is arguably the most outright alien & Codex Seraphinianus-like. Given the strange rotating designs (machines?), truncated pipes, islands, and odd causeways, it’s hard to see (at first, second and third glances) how this could be anything but irrational. Yet even so, those who (like me) are convinced that the VMs is a ‘hyperrational’ artefact are forced to wonder what method there could be to this jumbled visual madness. So: what’s the deal with this page? How should we even begin to try to ‘read’ it?

People have pondered these questions for years: for example, Robert Brumbaugh thought that the shape in the bottom left was a “clock” with “a short hour and long minute hand”. However, now that we have proper reproductions to work with, his claim seems somewhat spurious, for the simple reason that the two “hands” are almost exactly the same length. Mary D’Imperio (1977) also thought the resemblance “superficial”, noting instead that “an exactly similar triangular symbol with three balls strung on it occurs frequently amongst the star spells of Picatrix, and was used by alchemists to mean arsenic, orpiment, or potash (Gessman 1922, Tables IV, XXXIII, XXXXV)” (3.3.6, p.21).

Back in 2008, Joel Stevens suggested that the rosettes might represent a map, with the top-left and bottom-right rosettes (which have ‘sun’ images attached to them) representing East and West respectively, and with Brumbaugh’s “clock” at the bottom-left cunningly representing a compass in the form of the point of an arrow pointing towards Magnetic North. You know, I actually rather like Joel’s idea, because it at least explains why the two “hands” are the same length: and given that I suspect that there’s a hidden arrow on the “bee” page and that many of the water nymphs may be embellished diagrammatic arrows, one more hidden arrow would fit in pretty well with the author’s apparent construction style.

This same idea (but without Joel’s ‘hidden compass’ nuance) was proposed by John Grove on the VMs mailing list back in 2002. He also noted that many of “the words appear to be written as though the reader is walking clockwise around the map. The words inside the roadway (when there are some) also appear to be written this way (except the northeast rosette by the castle).” I’ve underlined many of the ’causeway labels’ in red above, because I think that John’s “clockwise-ness” is a non-obvious piece of evidence which any theory about this page would probably need to explain. And yes, there are indeed plenty of theories about this page!

In 2006, I proposed that the top-right castle (with its Ghibelline swallowtail merlons, ravellins, accentuated front gate, spirally text, circular canals, etc) was Milan; that the three towers just below it represented Pavia (specifically, the Carthusian Monastery there); and that the central rosette represented Venice (specifically, an obfuscated version of St Mark’s Basilica as seen from the top of the Campanile). Of course, even though this is (I think) remarkably specific, it still falls well short of a “smoking gun” scientific proof: so, it’s just an art history suggestion, to be safely ignored as you wish.

In 2009, Patrick Lockerby proposed that the central rosette might well be depicting Baghdad (which, along with Milan and Jerusalem, was one of the few medieval cities consistently depicted as being circular). Alternatively, one of his commenters also suggested that it might be Masijd Al-Haram in Mecca (but that’s another story).

Also in 2009, P. Han proposed a link between this page and Tycho Brahe’s “work and observatories”, with the interesting suggestion that the castle in the top-right rosette represents Kronborg Slot (which you may not know was the one appropriated by Shakespeare for Hamlet), with the centre of that rosette’s text spiral representing the island of Hven where Brahe famously had his ‘Uraniborg’ observatory. Kronborg Slot was extensively remodelled in 1585, burnt down in 1629 and then rebuilt: but I wonder whether it had swallowtail merlons when it was built in the 1420s? Han also suggests that other features on the page represent Hven in different ways (for example, the three towers marked ‘PAVIA?’ above); that the pipes and tall structures in the bottom-right rosette represent Tycho’s ‘sighting tubes’ (a kind of non-optical precursor to telescopes); that one or more of the mill-like spoked structures represent(s) Hven’s papermill’s waterwheel; and that the central rosette represents the buildings of Uraniborg (for which we have good visual reference material). Han’s central hypothesis (on which more another day!) is that the VMs visually encodes information about various supernovae: the suggestion here is that the ‘hands’ of Brumbaugh’s clock are in fact part of the ‘W-shape’ of Cassiopeia, which sits close in the sky to SN 1572. Admittedly, Han’s portolan-like ‘Markers’ section at the end of the page goes way past my idea of being accessible, but there’s no shortage of interesting ideas here.

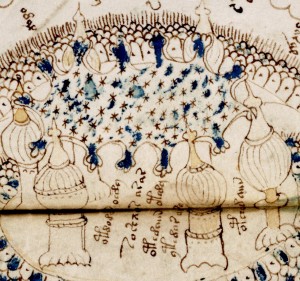

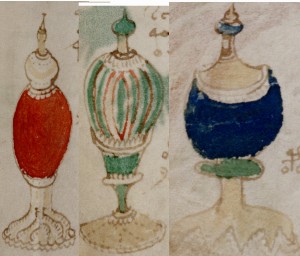

Intriguingly, Han also points out the strong visual similarity between the central rosette’s ‘towers’ and the pharma section’s ‘jars’: D’Imperio also thought these resembled “six pharmaceutical ‘jars'”. I’d agree that the resemblance seems far too strong to be merely a coincidence, but what can it possibly mean?

Finally, (and also in 2009) Rich SantaColoma put together a speculative 3d tour of the nine-rosette page (including a 3d flythrough in YouTube), based on his opinion the VMs’ originator “was clearly representing 3D terrain and structures”. All very visually arresting: however, the main problem is that the nine-rosette page seems to incorporate information on a number of quite different levels (symbolic, structural, physical, abstract, notional, planned, referential, diagrammatic, etc), and reducing them all to 3d runs the risk of overlooking what may be a single straightforward clue that will help unlock the page’s mysteries.

All in all, I suspect that the nine-rosette page will continue to stimulate theories and debate for some time yet! Enjoy! 🙂

I have to say that I’m pretty humbled by the hit stats for the Wikipedia Voynich page: when the xkcd webcomic spike happened in June 2009, the Voynich page got a quite shocking 77k hits in a single day. In fact, its daily traffic has gone up from 500-1000 hits at the start of 2009 to 1000-2000 hits as of now (May 2010) (though interspersed with occasional 10k days).

And so I wondered if it was just about time for Jim Davis’ Garfield to take on the Voynich Manuscript: if he did, might it look something like this?

For any passing lawyers, I’m neither passing this off as an original Garfield strip by Jim Davis nor trying to make money from his intellectual property, it’s just one of his strips unconvincingly hacked to show what my idea of a Voynich-themed Garfield strip would look like for the benefit of my Cipher Mysteries readers. And yes, I’ll happily take it down if you ask me to. 🙂

If I had a pound for each time I’ve been disparaging about the Wikipedia Voynich Manuscript article, I’d probably be able to pay off my mortgage: but this is not because I’m negative (when I’m actually the complete opposite), but rather because despite being the most-linked page in the whole Voynich infosphere (Google has it as #1, for example), it’s miserably unhelpful on a truly grand scale.

A few days ago, I decided to go through it to see how much of it I could fix… but after a while, what struck me was that I was just sticking plasters on a gaping wound – that there was something so badly wrong with the way it was structured that no amount of textual hacking would ever fix it. That is, the problem isn’t that it is awkwardly written, but that it is epistemologically broken. I therefore added a new section to the Wikipedia Voynich talk page to say:

[…] But on reflection, it strikes me that what is fundamentally wrong with the whole thing is that it doesn’t really separate objective from subjective; and furthermore that its overall structure helps perpetuate this mingling of fact and speculation. I think that if we were to restructure it more sensibly, we might yet turn this whole article into a genuinely useful resource, rather than the sprawling sequence of speculative stuff it currently is.

I therefore propose that before the (currently first) “Content” section, a new section should be added called “Evidence”, with suggested subsections “Codicology” (facts about the support material [including radiocarbon dating], inks, paints, construction, quire numbers, foliation), “Palaeography” (facts about the ductus, Currier ‘Hands’), “Art History” (techniques used in the construction, such as parallel hatching) and “Statistics” (facts about the letter-patterns and word-patterns). The idea is that by doing this, we can separate out the discussion of what the Voynich Manuscript is from the discussion of what the Voynich Manuscript might be, so that people coming to the topic for the first time can gain an accurate picture untainted by the currently rather high level of embedded speculation. My Cipher Mysteries pages on codicology, quire numbers, parallel hatching may well be fruitful references for some of these topics.

I have elsewhere contrasted the existing speculation-centric “Voynich 1.0” approach with this “Voynich 2.0” history-centric approach: though the main argument against this used to be that we knew too little about the Voynich Manuscript to produce a useful non-speculative introduction to it, my opinion is that this is no longer true. Yet however sensible this change may be from my perspective, it is almost certainly too significant a difference to impose unilaterally on a well-linked article without some kind of sustained debate here first. So… what do you think? Nickpelling (talk) 09:11, 20 May 2010 (UTC)

This is an issue that really affects our whole research community (rightly or wrongly, the Wikipedia page is seen as the front face of the Voynich Manuscript), so please leave your comments either here or by editing the Wikipedia talk page by hand (but log in first). Have I got this right, or do you think the page is just fine as it is?

Something further to reflect upon is the differentiation drawn by Michael Shermer in a recent New Scientist article: he draws a line between skepticism and ‘denialism’, in that ‘denialists’ start from an ideological point of faith and deny / undermine all the evidence that’s inconsistent (i.e. they support their own weak ideas by trying to weaken the evidence supporting other competing ideas), whereas skeptics (as Shermer is the publisher of “Skeptic” magazine, these are the good guys) use “extensive observation, careful experimentation and cautious inference” to separate “the few kernels of wheat from the large pile of chaff”.

Within this conceptual framework, it strikes me that the overall Voynich research programme has had a particularly denialist methodology:

- Find a starting point (usually a similarity between something in the VMs and something you happen to know about)

- Construct a personal leap of faith (“because these are similar, the VMs must have been written by…”)

- Collate all the miscellaneous scraps of evidence that seem consistent with your personal leap of faith

- Find rhetorical ways of being dismissive about all the other evidence that is broadly inconsistent

- Construct ways of undermining the methodology behind any conflicting evidence (“radiocarbon dating is inaccurate”, etc)

What Shermer omits, though, is that in the real world the trickiest issue of all is how to tell denialists apart from skeptics. After all, they use the same techniques and rhetorical stylistics: who can say where Popperian falsification stops and apologetics starts?

Actually: I can. Firstly, there’s a further division to be made between a cynic and skeptic, insofar as I think a cynic is a denialist whose own personal leap of faith is that “no theory is possible”: you can therefore think of a cynic as an ideological pessimist, who actively denies the possibility of there ever being an achievable answer. By way of comparison, a skeptic is optimistic enough to believe that an answer is possible, but realistic enough to know that the road to such knowledge can be a long and hard one.

To me, a skeptical methodology should be a far more holistic thing (insofar as its goes from the general to the specific), far closer to the kind of thing intellectual historians do:

- Collect all the relevant evidence you can

- Find ways of assessing the reliability, pliability, and nature of each of them

- Assess (and continually reassess) which are the key pieces of falsifying evidence – the ones that let you reject hypotheses

- Construct a number of hypotheses that your key falsifying evidence pieces do not manage to kill

- Devise research questions to try to limit / constrain / refine / kill your hypotheses

- Keep trying (knowledge is hard)

The central differences are therefore (a) the overall direction of research, (b) skeptics understand that most evidence is not absolute, and (c) that skeptics attempt to invalidate all hypotheses, rather than just confirm their own. Further, skeptics know that correlation is not the same as causation, and that causation is 100x more elusive. So… are you a skeptic, a cynic, or a denialist?

Applying all this to the Wikipedia VMs page, at no point does the article try to collate or list all the relevant evidence, or even to give an idea of how reliable or (im)precise each fragment is. Rather, it seems to be a long sequence of theories abutted by denialist oppositions to them. Given that my bias is towards the kind of skeptical methodology I describe above, my overall position is that the page offers little or no assistance to someone who comes in and wants to understand the object prior to forming an opinion: rather, the page offers a load of pre-formed opinions and rebuttals, with fragments of information teasingly wedged between them. It’s rather like trying to understand wildebeest anatomy by looking at the scraps of meat left on a lion’s teeth.

Perhaps I’m barking up completely the wrong tree here: perhaps the “Wikipedia” model for knowledge is innately denialist, in that each article seeks to find a position of dynamic balance between actively-held apologetic positions. I suspect that the epistemological error underlying Wikipedia is that it mistakes a Mexican stand-off for consensus, when skeptical knowledge should ultimately be organized in a quite different way: all the Voynich article does is to highlight this error in a fairly extreme way.

What do you think – can Wikipedia ever be fixed?

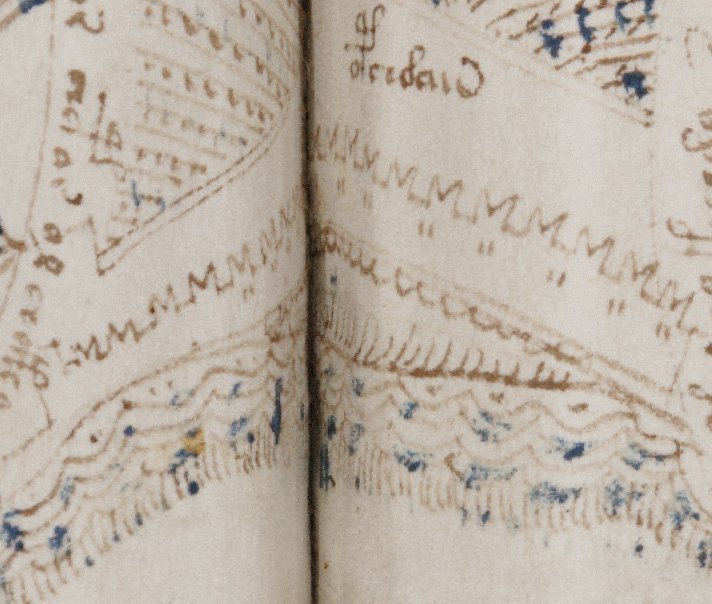

It’s not widely known that the Voynich Manuscript’s “nine-rosette” foldout page contains two sets of swallow-tail merlons – one set on top of the famous castle (as per the Cipher Mysteries header graphic), and one on a long low wall, apparently beside the sea. This latter runs across one of the folds, making it very slightly awkward to make out:-

But where is this? I suspect it’s not Genoa, because (as per this picture from Hartmann Schedel’s 1493 Weltchronik) that had neither a flat sea frontage nor swallowtail merlons. For a while I suspected that it might depict Naples: but while reading up on the Occitan dialect Niçard, I found a, well, nice picture of Nice being besieged from the sea by Barbarossa in 1543. The (fabulously made-up) story goes that outraged local washerwoman Catherine Ségurane climbed on top of the walls to expose her ample rear to the Turkish fleet, which (somehow) caused them to abandon their attack (Ségurane’s triumphant mooning is celebrated on November 25th [St Catherine’s Day] each year in Nice)… but I guess you had to be there. Anyway… because of Turin’s history as a key part of the Duchy of Savoy, the Biblioteca Reale di Torino also has quite a few piante e disegni of Nice AKA ‘Nizza’ (see p.508 of this online inventory, though unfortunately few dates are given), which might prove to be a useful resource. I don’t know whether or not all this line of thought is going anywhere: it’s certainly something to bear in mind, though.

I also found a nice picture of the same Turkish fleet wintering in Toulon, a mere 100 miles down the coast: it’s hard to be sure, but it looks to me as though its walls have swallowtail merlons. Were there any more major walled ports circa 1400-1450 between Marseille and Genoa? Perhaps Villefranche-sur-Mer? Someone out there should know…

I can’t claim to read your busy modern brain: but there’s certainly a moderate chance that you just happen to dig both FBI profiler police procedural drama “Criminal Minds” and the Voynich Manuscript. If so, you may well be pleased to know that madlori (just don’t call her ‘lady’, ok?) has just posted part 1 (of 4) of her Voynich-themed “Criminal Minds” fanfiction, entitled “The Mysterious Manuscript”, focusing mainly on FBI BAU Supervisory Special Agent Emily Prentiss and her Voynich nerd husband Reid.

Now, according to the last round robin I got from the Bloggers Union, this is the point where I’m supposed to go all snarky about fanfiction, and moan about how Kirk and Spock wouldn’t really have kissed, particularly with tongues (ergo all fanfiction is pants) etc. But actually, it turns out that dear Lori isn’t half as mad as she’d like to think she is (bless ‘er), and she’s done a pretty good job overall (so hopefully parts 2-4 will be better still). Of course, her plexiglass case around the VMs is just hokum, New Haven isn’t half as miserable as she makes it sound, and the Beinecke curators weren’t anything like as sniffy when I went on my own three-day VMs hajj: but maybe things have changed since I was there. 🙂 Still, I’d forgive her plenty for casually slipping verklempt into the text: already I feel bad about kvetching. So shoot me!

Perhaps because of its geography (spanning a mountain range) or its powerful neighbours (France, Milan), Savoy is one of those nebulous, hard-to-grasp historical regions with a perimeter seemingly made of rubber.

Here’s a map of 15th century Savoy courtesy of the very useful sabaudia.org: as landmarks, you can see Milan, Turin, Genoa and Lyon – just off to the lower left are Marseille and Avignon (home to antipope Clement VII and antipope Benedict XIII between 1378 and 1403, at which time the latter escaped to Anjou following a five-year siege by the French army). The green shapes mark mountain passes:-

The same site also has a nice timeline for Savoy events (in French), from which I’ve summarized a few points of interest between 1350 and 1450 below. The initial historical context is that Amadeus VII is ruling the House of Savoy, with the separate Savoy-Achaia line ruling over Piedmont (but please don’t ask me to summarize the history of Achaia and how it’s linked here, that might well bore you to death):-

- 1385: Amadeus VII acquires the Barcelonnette region.

- 1388: Amadeus VII loses Nice to Jean Grimaldi.

- 1401: Amadeus VIII acquires the County of Geneva after the last Count Humbert dies childless.

- 1403: Louis of Savoy-Achaia moves the House of Savoy’s capital to Turin, and creates the University of Turin as part of the first State of Savoy.

- 1406: Amadeus VIII receives the homage of the Seigneur de la Brigue and negotiates with the Count of Tende to establish a direct route between Nice and Turin.

- 1411: Amadeus VIII buys Rumilly, Roche, and Ballaison, the House of Geneva’s last remaining possessions.

- 1411: The Savoyards briefly occupy the Val d’Ossola to ensure control of the Simplon pass (though the Swiss Confederates subsequently drove them out in 1417).

- 1416: after a magnificent reception at Chambery, the Emperor Sigismund, visiting Amadeus VIII for the third time in four years, grants him the ducal title – the House of Savoy become the Duchy of Savoy.

- 1418: following the last Savoy-Achaia’s death, Amadeus VIII regains control of Piedmont.

- 1427: the Visconti yield Vercelli to Amadeus VIII.

- 1434: Louis of Savoy marries Anne of Lusignan in Chambery, a union which binds the Savoy royal family to the Lusignan kings (from Cyprus and Jerusalem) & hints at an Eastern policy for the Duke.

From this, you can see the shadow of the Holy Roman Empire hanging over the legitimacy of the House of Savoy’s 1416 transition to become the Duchy of Savoy: so it is should be no surprise that if you look at the rear of Turin’s Palazzo Madama (which was started by the Savoy-Achaia line in the 14th/15th century), you can still see make out its swallowtail merlons embedded just below the top of its towers.

Now all this historical framework is in place, you should be just about able to make some sense of this hideously overcomplex historical map of Savoy (from William Shepherd’s Historical Atlas of 1923-1926), courtesy of the University of Texas at Austin.

For my own Voynich Manuscript research, what has become clear to me from this is that rather than Savoy in the larger sense, it is probably Piedmont (as gained by the Duchy of Savoy in 1418) I should be specifically interested in. But what Piedmontese historical archives should I be looking at? Questions, questions, questions…