There are colours in my eyes, history flickering and sputtering as a beautiful infinity reaches out to hold my bloodsoaked hand…

* * * * * *

The Brazilian girl’s plan is stone-cold in its vision, fractal in its detail, awesome in its thinking. Yes, the organizers have put the necessary overnight protection squad in place: but the two guards merely notice a curious mélange of hard-to-pin-down antique odours: spirit of hartshorn, hepatic air, green vitriol, all distinct yet merging awkwardly between one another, like jelly and ice cream in a child’s pudding bowl. They both feel the nausea slowly roll over them, but neither thinks to raise the alarm, as the aqua tofani weaves its dizzying, nauseous, near-fatal spell on them both. Of course, we don’t intend killing them: tonight’s sacred mission is one of life, not death.

Our filter masks firmly in place, we silently ease out of the concealed block behind the disabled toilets and past the sabotaged air-conditioning unit. The girl’s preparation has been good, for there is no klaxon, no lights, no alarm: following her confident lead, I guide the wheely bag carefully past the two tumbledown security-suit mannequins and onwards through the exhibition. Looking ahead, always ahead, we glide swiftly past countless Ouroubos-filled stands and up the wheelchair ramp to the locked glass plinth in the arena’s central raised area – yes, to the book. Or rather, to ‘The Book’.

She reaches into her pocket and pulls out the diamond-edged ring we made together over the shimmering orange dawn-lit fire on the mountainside: looking in her eyes, I take it and slide it quickly onto my middle finger. The girl – is she young, or old? Suddenly I can’t tell any more – nods, flicking her renegade, emptily-hungry eyes at me, and deftly touches my shoulder, her fingertip feeling for all the world like a butterfly landing and quickly gently launching itself away, far away into the curious half-light. On cue, I turn my attention to the security glass, and carefully use the hard-edged symbol of our union to etch its front face with four good-size concentric circles.

The hall is starting to fill, now: our small army of alchemists is emerging one by one from their hiding places behind occult bookstalls, beneath pagan stall covers and carefully-positioned wizard cloaks, each with a red or yellow hood and a surgical mask tightly fastened down, just as she had specified. As the last of the twelve completes the circle around us, I step sharply forward and punch the ring’s diamond tip right at the centre of the design. The glass buckles a little, yet doesn’t quite give way – No, I think, something is wrong, and for an instant a cloud of burnt cinnamon doubt swirls around me, enveloping me in the riptide of fears I’ve worked so hard to suppress these past three years.

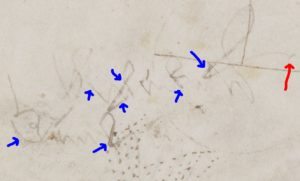

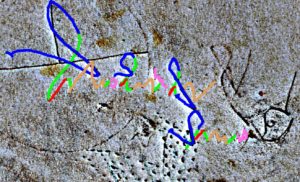

Yet perhaps sensing my edginess, the alchemists start to clap and chant, and before long I feel their resolve coursing through my veins. The bull in my soul charges forward and I punch, punch, punch the toughened glass until it starts to yield to my attacks, and its etched central circle finally gives way. Impatiently, I widen the glassy gap with my bare hands just enough to remove the book and to raise it over my head in triumph, tersely spattering its centuries-rigid vellum cover with my blood as I do so. The alchemists swoop in too to hold it aloft and to turn it to The Page, that one, marvellous page we have been waiting to see all our lives.

I look over to the girl: she nods once again and I bring out the ceremonial firebowl from the bag. Adam – dear, ever-reliable Frater Adamus – deftly removes the page with his pocket knife, folds it to shape, fills it with regulus of antimony, and ties up its gathered top using aqua vitae-impregnated handmade blue twine from his workshop. We are all trembling now, for everyone (even Baresch) was right – the Philosophers’ Stone is indeed hidden inside The Book: yet this is neither a metaphorical truth nor a pharmacological truth, but instead a literal truth. For once you have – as we have, over so many decades – worked to decode its carefully layered and allusive visual symbolism, the Voynich’s pages form a map spiralling in on itself… all pointing to one place, the single slightly-thicker-than-average vellum herbal bifolio inside which the tiny fragments of Stone were sealed all those centuries ago. We, then, are its 21st century liberators, its alchemical revolutionary freedom front: all we have to do now is light the blue touchpaper, and see the long-promised fireworks. And this ceremony marks the end of alchemy’s epic struggle, the chequered flag at the finishing line of two millennia of The Work. My queen nods once more for me to step forward with my lit taper, so that we can all make the ultimate step – beyond History, beyond pain, beyond Time itself. And I do, but…

* * * * * *

There are colours in my eyes, history flickering and sputtering as a beautiful infinity reaches out to hold my bloodsoaked hand… In this moment, I don’t know if I’m living forever or dying forever, if the girl is really human or some selfish dark spirit that is guiding me I know not where. Am I releasing her or creating her? Is she part of me or am I part of her? A flash from the the burning vellum page suddenly lights up our faces and I lay down beside her on the floor, the alchemical king and queen finally together, just as the Ancients foretold. A fire alarm finally goes off, its sprinklers lurch into action with a indoor cloudburst, but it is all too late, far too late, the Stone is here, The Stone Is Here! For all the burning, twisting sensations, we know for certain that the Stone is merely giving us a taste of ultimate Death to deliver its promise of ultimate Life. Yet though the colours in its flames are more intense than ever now, so too is the agony: I turn to the girl and see the same things I’m feeling reflected in her sprinkler-soaked face, and as we hold each other tightly I know it is both the end and the beginning, and our eternal future together lies in and beyond the Stone…

* * * * * *

Why on earth, mused the firemen, policemen, and paramedics, would anyone have gone to the trouble of placing all those strangely-posed lifelike statues in the middle of the hall? And why was just a single page missing from the precious Voynich Manuscript, on a rare two-day loan to this alchemy conference? File it under ‘M’ for ‘mystery’…