Here’s a curious object I hadn’t seen until a few days ago that fulfils pretty much all the cipher mystery criteria: unknown symbols (check), mysterious drawings (check), wobbly provenance but still genuinely old (check), a well-respected person making a fool of himself by radically misinterpreting it (check), etc.

The book known as “Le Livre des Sauvages” is (or was) MS 8022 in the Bibliotheque de l’Arsenal in Paris, and was the subject of an 1860 study by a solid (if not actually stolid) apostolic missionary to North America, Abbe Em. Domenech. Unfortunately, Domenech’s plausible-sounding theory (that this was a kind of curious Native American document) found itself torpedoed almost immediately by a whole bunch of German critics, who pointed out a good number of German words (the ‘ss’ is a bit of a giveaway) inserted into the pages in a rather unsophisticated hand:-

1. anna; 2 et; 3. maria; 4. ioanness; 5. will; 6. gewald; 7.grund; 8. et; 9. word; 10. gern; 11. heilig; 12. hass; 13.gewullsd; 14. wurssd; 15. nicht wohl; 16. ssbot (spott); 17. unschuldig; 18; richen schaedlich; 19. feirdag; 20. heilig ssache; 21. winiger (weniger); 22. bedreger (betrueger); 23. zornig gessdeld; 24. gott mein zeuge; 25. bei gott.

So, by about 1865 the mainstream opinion of Le Livre Des Sauvages became that its bizarre pictures and odd text were merely the doodlings of a German-speaking child, “[un] cahier de barbouillages d’un enfant” in the words of one critic, and his conclusion that “Ceci est d’une veritie incontestable” is where things basically remained until the present day.

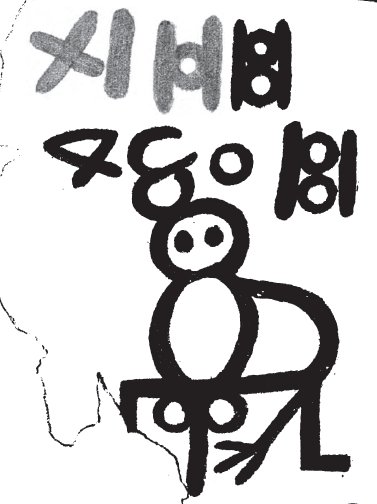

But (as I’m sure you’ve already guessed) I’m not actually so sure. You don’t have to go far through Le Livre Des Sauvages before you build up an idea of the – clearly adult, I’d say, and clearly disturbed – pictorial language in its pages. Basically, its mouthless stickfigures seem to me to have been constructed mainly to express the male author’s numerous troubled sexual obsessions.

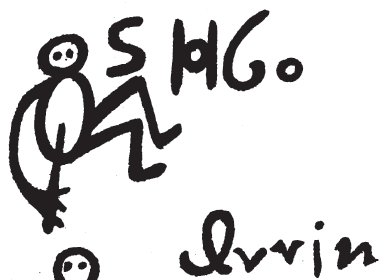

At this point, just in case you think I’m perhaps projecting my own psychodramas onto some poor book’s blank cryptographic screen, it’s time to include some graphic images from Le Livre. Look away now if you’re easily offended!

The author’s thoughts clearly range from down days (p.6)…

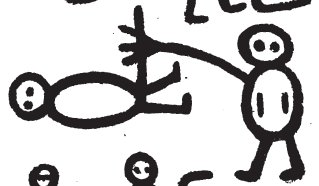

…to, let’s say, cooperative days (p.31)…

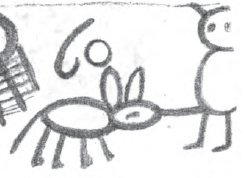

…and indeed very cooperative days (p.31)…

Other recurrent themes involve putting things in certain places (p.33)…

…quite the wrong kind of ‘petting’ (p.50)…

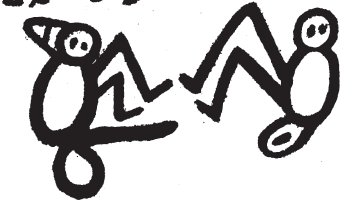

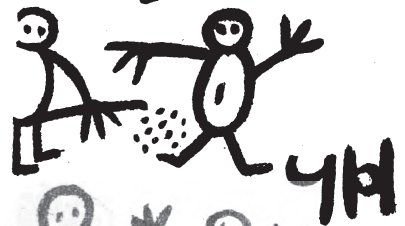

…and, let’s say, delivering on his promises (p.37)…

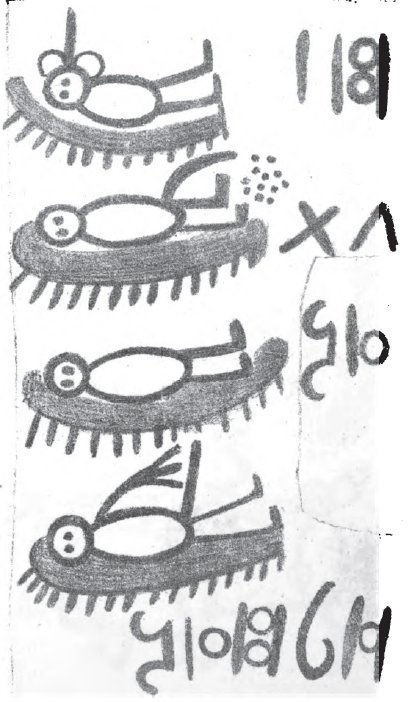

Helpfully, the author puts many of these together in a single (apparently night-time) sequence which presumably shows how many of these activities go together for him, starting with having certain thoughts on his mind (p.70):-

And so on, for several hundred pages (I kid you not). Parallel to all this visual angst, there are (as you can see in some of the above pictures) small snatches of cipher-like material. So yes, this is almost certainly a cipher mystery, though not one for which I can find a decent modern archival reference, nor an codicological study.

But frankly, unless a cipher historian with a particularly strong interest in psychosexual hangups steps forward, I don’t think anyone is going to try, ummm, hard to decipher this little oeuvre: basically, even if you can’t read the words, you probably can get the overall picture. 🙂