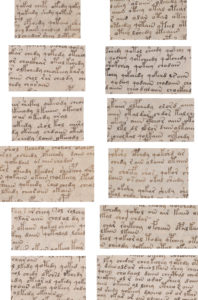

In a recent post, I discussed a large number of features of the Voynich Manuscript’s Quire 20, to try to get under its vellum skin (so to speak). One thing I’d add is that if you compare the vellum colour of the front (recto) and back (verso) of pages f103 through to f108…

…you can see (I think) if you constrast enhance these…

…that f104, f105, f107 and f108 appear to match each other quite well.

Hence – given that I think f103 may well be separate anyway – I infer from this that f104, f105, f107 and f108 may well have been folded and cut from a single piece of vellum: and hence that they might very well have sat next to each other in Q20’s alpha state. Hence f106 and the missing f109-f110 bifolio may well have been from a different piece of vellum, and so (given that I suspect f105r was the first page of the book hidden in the quire) may well together have formed the two most central bifolios of the quire.

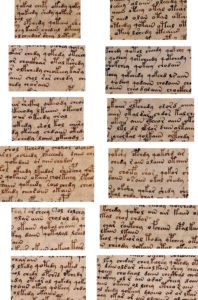

So: given all the above, and that there seems to be a good chance that f108v and f104r originally sat next to each other (as discussed before), I suspect we now know enough to reduce the large list of bifolio permutations for Q20’s original state down to just four good candidates (I’ve only listed the first folio of each bifolio pair for convenience):

a) f103 : f105 f108 f104 f107 f106 [f109]

b) f103 : f105 f108 f104 f107 [f109] f106

c) f103 : f105 f107 f108 f104 f106 [f109]

d) f103 : f105 f107 f108 f104 [f109] f106

Of course, I may be wrong… but I do now think there’s a high chance that this is basically correct.

But to use the block-paradigm trick (i.e. to decrypt a cipher by finding a separate copy of the text from which it came) with these possible candidates, though, we need to also find a structurally matching copy of the hidden book’s plaintext.

So the big question is surely this: how on earth do we find a copy of Quire 20’s plaintext?

Johannes Alcherius

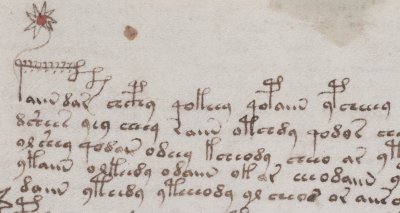

Elsewhere in Cipher Mysteries, I mentioned BNF MS Latin 6741, which is a collection of 359 recipes collected together in Paris by Jean le Bègue / Jehan le Bègue in 1431, and which was discussed by Mary Merrifield in her 1849 book Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, on the Arts of Painting.

Yet having now read in rather more depth about Jean le Bègue’s recipe collection here, I suspect that the answer lies not in Paris (the city which BNF MS Latin 6741 seems never to have left) but instead in Milan, and specifically with Johannes Alcherius – arguably the key author whose recipes Jean le Bègue ripped off collected together.

However, the big problem is that while Alcherius wrote in Italian, Jean le Bègue wrote in Latin – so what we have in BNF MS Latin 6741 is actually a Latin translation of Alcherius’ Italian original.

So if I’m right about this, it would mean – unfortunately – that rather than finding the Italian plaintext from which I believe a large part of Quire 20 was derived, I strongly suspect that BNF MS Latin 6741 instead contains Jean le Bègue’s Latin translation of that same Italian plaintext.

So… even though I suspect that the block paradigm trick may have got me close to the finishing line in this instance, the Voynich Manuscript’s secrets still continue to elude us. Close, but no cigar. Or pizza. Oh well! 🙁

How to cross the Quire 20 line?

It seems to me that the single most important piece missing from this jigsaw is the Italian plaintext of Johannes Alcherius’ recipes for colours. I can see two possible routes to achieve this:

(1) Reverse translate Jean le Bègue’s Latin back into the Italian plaintext from which it was derived. Which would be exquisitely nuanced, and very hard to get right, but just about possible all the same. Or…

(2) Find fragments of Alcherius’ recipes floating in other documents, but in their original Italian form (rather than in Jean le Bègue’s Latin translation). It may be that, somewhere in the far recesses of Academe, someone has already searched for this, perhaps as part of a compeletely separate study. But if so, my own digging has been utterly unable to find it.

Perhaps you will have better luck, though!

Things you can help with

Does someone have (or can get access to) a PDF copy of “The recipe collection of Johannes Alcherius and the painting materials used in manuscript illumination in France and Northern Italy, c. 1380-1420” (1998) by Nancy Turner that they can send me, before I start throwing my money at Maney Online (now part of Taylor & Francis)?

Or a copy of “Painting Techniques : History, Materials and Studio Techniques, Proceeding of the IIC Dublin Congress, 7-11 December 1998”, where the same thing also seems to appear?

Or… does anyone have a study listing all pre-1500 Italian colour recipe manuscript fragments? (For what it’s worth, I was unable to find any mention of Alcherius or Jean le Bègue in Thorndike.)