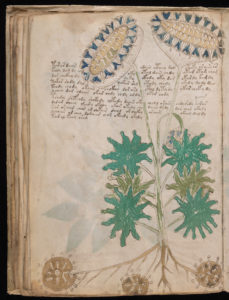

Every couple of years, I wake up in the middle of the night with an all-new version of The Big Idea – you know, the one that’s finally going to unlock the Voynich Manuscript’s secrets. These unstoppable small-hours plans are normally formed from the soup of things slooshing around in my head, but arranged in a pincer movement attacking the problem on two fronts (i.e. with the idea of trapping it in the middle).

As an aside, it would be a bit of a shock to me if the Voynich Manuscript’s contents turn out to be something wildly unexpected, like a 200-page Swahili ant-summoning ritual, or a book about various weird vegetables that magically cure diabetes (as if anyone would randomly send emails about that, ho hum). :-/ Similarly, I would find it a big surprise if the writing / enciphering system were to turn out to be something we hadn’t collectively considered at length and in detail already, though in some cunning combination that we hadn’t quite grasped.

More generally, I would summarize my overall position as being that, without much doubt, there is a high probability that we are much closer than we think to the Voynichian chequered flag. Even though there are many nuttier-than-a-fruitcake researchers out there (no, I’m not referring to you, dear reader, that would be quite absurd), a huge amount of excellent research has been done, a very large part of which will almost certainly be correct.

And so, swimming against the pessimistic epistemological tide that seems to prevail these days, my overall judgement is that we shouldn’t – very probably – need to know much more than we already do in order to crack through the Voynich’s walls: just a little more may well do the trick. In fact, it may even be that a single solid fact might be enough to open the floodgates. 🙂

This Week’s Big Idea

And so it was that I woke up at 2am a few nights ago with (inevitably) a new Big Idea for cracking the Voynich. And given that my last post was about the diffusion of vernacular Cisiojanus mnemonics, I guess few readers here will be surprised that the main part of the idea was that the 30-odd labels per zodiac sign might well be the syllables of a vernacular Cisiojanus.

Why vernacular? Well, even though Latin Cisiojani had been known since the 12th century or so, vernacular Cisiojani were novel and unknown even in the mid-fifteenth century, and so one might well be a good candidate for something someone compiling a book of secrets might well want to conceal / hide / obfuscate / encrypt (delete as appropriate).

At the same time, I don’t believe that Voynichese can be enciphered or obfuscated Latin, because the way Voynichese seems abbreviated / truncated seems incompatible with Latin (where endings contain so much of the meaning). But if we are instead looking at a linguistically diffused Cisiojanus (such as Italian or French), it’s perhaps a different kettle of (cray)fish.

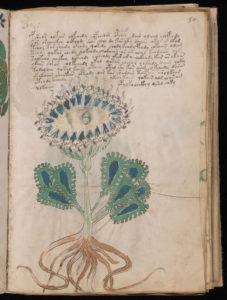

In parallel, the Voynich zodiac section offers us numerous more interesting clues to work with: for instance, the three crowned nymphs, of which the red-crowned nymph on the Leo page is arguably the earliest.

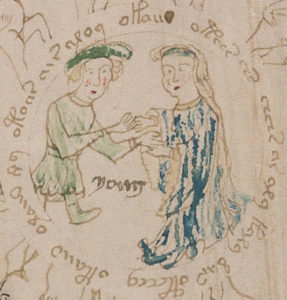

I’ve previously proposed that one or more of these crowns might be flagging a feast day with personal significance to the author. (For example, for a Florentine such as Antonio Averlino, the most important day in the calendar was the Festa di San Giovanni, the Feast of St John the Baptist.) As such, we might also look at the Voynich zodiac page for Cancer, which also has a crowned nymph, but where the crown looks to have been added later:

I previously mused whether this Cancer crown might have been a fake, designed to draw attention away from the real crown in Leo, but in retrospect this was a bit too harsh and reductive, even if the codicology is sound. Rather, these two crowns (and indeed the crowned nymph in Libra) may well have had different types of significance, added in separate codicological layers for separate reasons. Even if the idea of Antonio Averlino’s connection to Firenze is too strong for some of you, the connection between Italian Cisiojani and St John the Baptist may still be worth pursuing, as we’ll see next.

Nicola De Nisco’s Cisiojanus

In the same way that Jesus’ birthday is celebrated near the Winter Solstice (the shortest day of the year), St John the Baptist’s birthday is celebrated near the Summer Solstice (the longest day). And so it has been widely suggested that both attributed birthdays offered Christian hooks to hang pagan festivals from (and there seems to be no obvious reason in the Bible why John’s birthday should be celebrated then). Hence in many places in Europe (not just Firenze), the Feast of St John the Baptist was a three- or four-day long affair, arguably more akin to a pagan summer festival.

Hence if we suspect that the labelese text in the Voynich’s zodiac section is some kind of vernacular Cisiojanus, there should be plenty of good reasons why we should look for the Feast of St John the Baptist.

For June (which German calendars typically link with Cancer), De Nisco transcribes one 15th century Italian Cisiojanus as follows:

Nic.mar.cel.qui.bo.ni.dat.me.pri.mi.bar.na.an.ton.

Vi.ti.que.mar.pro.ta.si.san.ctus.io.bap.io.do.le.pe.pau

If we add in De Nisco’s corrections in square brackets, plus additional saints’ names courtesy of that most indispensable of publications, The American Ecclsiastical Review (1901), Vol. 24, plus an 1886 French book which gave me St Dorothy of Prussia), we get:

1. Nic — Nicomedes [original document has “Vic”]

2/3. mar.cel — Marcellus / Marcellinus

4. qui — St Quirino, Bishop of Sisak

5/6. bo.ni — Bonifacius

7. dat — ???

8. me — Medardus

9/10. pri.mi — Primus

11/12. bar.na — Barnabas

13/14. an.ton — Sant’Antonio da Padova

15/16. Vi.ti — Vitus

17. que —

18. mar — Marcus et Marcellianus [original document has “Nar”]

19/20/21. pro.ta.si — Protasius (et Gervasius)

22/23/24/25. san.ctus.io.bap — St John the Baptist

26. io — Johannes (et Paulus)

27. do — (if this isn’t St Dorothy of Montau (Prussia), patron saint of the Teutonic Knights (from 1390) whose actual feast day should be 25th June, who was it? Thanks Helmut Winkler for pointing this out.)

28. le — Leo

29. pe — Petrus et Paulus

30. pau — Commemoratio Pauli

The presence of the much-contested St Dorothy of Prussia (a chronically-self-harming widow from near Gdansk, who was adopted in the 20th century by Catholics for Hitler, if you really want to know) gives us a hint not only to the German origins of this particular Cisiojanus, but also an earliest date (1390). Yet the presence of St Quirino perhaps hints at an itinerary via Hungary (the St Quirino with a 4th June feast died in Szombathely, whereas the St Quirino of Rome had an entirely different feast day): while, as De Nisco points out, the presence of the Feast of Sant’Antonio da Padova points very strongly to a Paduan Ciosiojanus adapter.

More importantly, you can see “san.ctus.io.bap” taking up four consecutive syllables in the Cisiojanus, a fragment of (almost-)plain text peeking through the jumble of syllable fragments that make up the rest. Moreover, the next syllable along is also “io” (for the feast of St John and St Paul), which might also be there for the finding.

All of which could offer an excellent crib for the plaintext lurking somewhere beneath Voynich’s labelese: so might we be able to find some echo of this in the Cancer labelese? Even more remarkably, might we be able to line up this phrase’s syllables with the labelese close to the crowned nymph in Cancer?

(As an aside, I hope you can see that this is the kind of connection that not only wakes Voynich researchers up in the night but also stops them from getting back to sleep.)

The “san.ctus.io.bap” Crib

Firstly, I offer up my own EVA transcription of the Voynich Cancer labels:

Outer ring (from 10:00 clockwise, just around from a gap at the left)

ykalairol

olkylaiin

olalsy

or.aiin.am

os.as.sheeen

otosaiin

opoiinoin.al.ain

ypaiin.aloly

oteey.daiin

oeeodaiin

ofsholdy

opoeey.okaiinCentral ring (from 10:00 clockwise)

olfsheoral

or.alkam

ytairal

oeeesaiin

ory

ochey.fydy

ofais.oeeesaly

ykairaiin.airal

okalar

orary

olaiin.olackhyInner ring (from 09:00 clockwise)

oletal

opalal

yfary

osaiisal

ytoar.shar

actho

aral

And then I offer up my thoughts: much as this whole idea got between me and my comfortable bed, I just can’t construct a sensible mapping (even with verbose cipher) between these labels and any of the Cisiojani I’ve seen, whether Latin, Italian, French or whatever.

But then again, I can’t sensibly map these labels to just about anything, language-wise: there’s no structure, or grammar, or variational consistency that offers a way of systematically parsing these labels into a system, let alone reading them. Even the characteristically labelese-like “oletal” / “opalal” / “okalar” / “olalsy” words (I’d perhaps also include “osaiisal”, “otosaiin”, “oeeesaiin” and “ytairal” in this group, and maybe even “ykalairol” and “olkylaiin” too) are only a minority of the thirty labels.

All of which isn’t to imply (as Richard SantaColoma is wont to say) that ‘this can only be a hoax’ (*sigh*), but rather that I think we’re missing something really big here, a rational connecting principle that would give these kind of labels a mutual structure and explanatory context that our theoretical crossbow bolts are flying a mile both over and past. For example, what is the way that we see “es” (411) much more than “er” (28), or “ir” (724) much more than “is” (62) really telling us? Why is almost every single instance of “ssh” not only at the start of a word, but also either at the start of a line or immediately to the right of an illustration in the text?