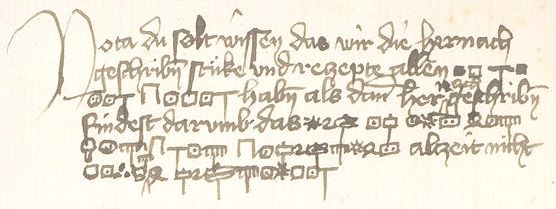

For ages, I’ve been planning to devote a day at the British Library solely to the task of looking for matches for the Voynich Manuscript’s unusual quire numbers. There’s a long description of these quire numbers elsewhere on this website, but the short version is that they are “abbreviated longhand Latin ordinals in a fifteenth century hand”, and are one of the key things that point directly to a 15th century date:-

If we could find any other manuscripts with this same numbering scheme (or possibly even the same handwriting!), it would be an extraordinarily specific way of pinning down the likely provenance of our elusive manuscript, more than a century before its next mention (circa 1610). It would also give an enormous hint as to the archive resources we should really be looking in to find textual references to it.

But let’s not get too carried away – how should we go about finding a match, bearing in mind we haven’t even got one so far?

To achieve this, my (fairly shallow, I have to say) research strategy is to trawl through the following early modern palaeography source books, as kindly suggested by UCL’s Marigold Norbye:-

- F. Steffens, Lateinische Paläographie (Berlin and Leipzig, 1929)

- New Palaeographical Society Facsimiles of Manuscripts &c., ed. E.M. Thompson, G.F. Warner, F.G. Kenyon and J.P. Gilson, 1st er. (London, 1903-12); 2nd ser. (London, 1913-30)

- Palaeographical Society Facsimiles of Manuscripts and Inscriptions, ed. E.A. Bond, E.M. Thompson and G.F. Warner, 1st ser. (London, 1873-83); 2nd ser. (London, 1884-94)

- S.H. Thomson, Latin Bookhands of the Later Middle Ages (Cambridge, 1969)

- G.F. Hill, The Development of Arabic Numerals in Europe exhibited in sixty-four Tables (Oxford, 1915)

- Catalogue des manuscrits en écriture latine portant des indications de date, de lieu ou de copiste, by Charles Samaran and Robert Marichal. etc.

To which I would add (seeing as it was written by Michelle Brown, who was for many years the Curator of Medieval and Illuminated Manuscripts at the British Library, so it seems a little ungracious not to include it)…

- Brown, Michelle. A Guide to Western Historical Scripts: From Antiquity to 1600. London : British Library, 1990.

…as well as the Italian equivalent of Samaran and Marichal’s work…

- Catalogo dei manoscritti in scrittura latina datati o databili per indicazione di anno, di luogo o di copista. Torino, Bottega d’Erasmo, 1971 Bird-Special Collections Z6605.L3 C38 f

…and a more general bibliographical reference work…

- Boyle, Leonard E. Medieval Latin Palaeography: A Bibliographical Introduction. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984.

Even though this might seem like a very large set of source books to get through in a day, no more than 5-10% of each is likely to be acutely relevant to the 15th century, so it should all be (just about) do-able. And I think that several of them may well be on open shelves in the Rare Books & Manuscripts Room at the BL, which should help speed things along.

Yet all the same, do I stand any significant chance of uncovering anything? Well… no, not really, I’d have to say. But that’s no reason not to try! And the bibliographic side of the trawl may well yield a more specific lead to follow in future, you never know.

All I need to do, then, is to free up an entire day from my diary… oh well, maybe next year, then. =:-o