Self-professed Voynich skeptic Elmar Vogt has been fairly quiet of late: turns out that he has been preparing his own substantial analysis on his “Voynich Thoughts” website of the Voynich Manuscript’s teasingly hard-to-read marginalia, (with Elias Schwerdtfeger’s notes on the zodiac marginalia appended). Given that Voynich marginalia are pretty much my specialist subject, the question I’m sure you want answered is: how did the boy Vogt do?

Well… it’s immediately clear he’s thorough, insofar as he stepped sequentially through all the word-like groups of letters in the major Voynich marginalia to try to work out what each letter could feasibly be; and from that built up a kind of Brumbaugh-like matrix of combinatorial possibilities for each one for readers to shuffle to find sensible-looking readings. However, it also has to be said that for all of this careful (and obviously prolonged) effort, he managed to get… precisely nowhere at all.

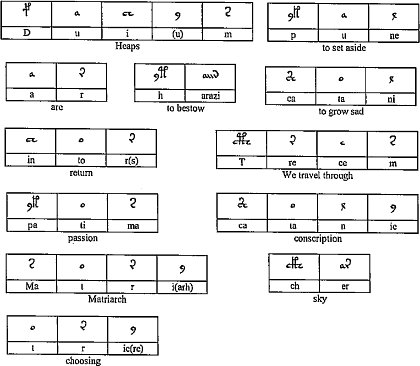

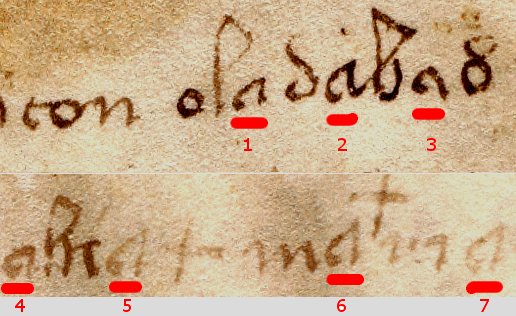

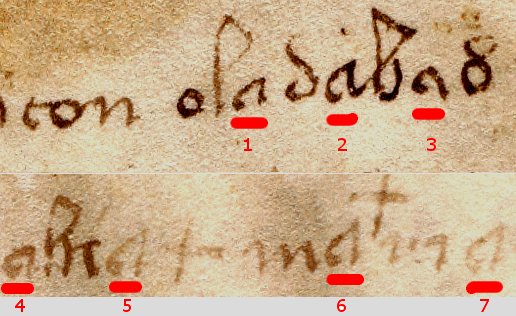

You see, we’ve endured nearly a century’s worth of careful, rational people looking at these few lines of text and being unable to read them, from Newbold’s “michiton oladabas“, through Marcin Ciura’s mirrored “sa b’adalo No Tich’im“, and all the way to my own [top line] “por le bon simon sint…“. Worse still, nobody has even been able to convincingly argue the case for what the author(s) was/were trying to achieve with these confused-looking marginalia, which can easily be read as containing fragments of French, Occitan, German, Latin, Voynichese (and indeed of pretty much any other language you can think of).

And the explanation for this? Well, we Voynich researchers simply love explanations… which is why we have so many of them to choose from (even if none of them stands up to close scrutiny):-

- Pen trials?

- A joke (oh, and by the way, the joke is on us)?

- A hoax?

- A cipher key?

- Enciphered text?

- Some kind of vaguely polyglot text in an otherwise unknown language?

How can we escape this analysis paralysis? Where are those pesky intellectual historians when you actually need them?

I suspect that what is at play here is an implicit palaeographic fallacy: specifically the long-standing (but false) notion that palaeographers try to read individual words (when actually they don’t). Individual word and letter instances suffer from accidents, smudges, blurs, deletions, transfers, rubbing off, corrections, emendations: however, a person’s hand (the way that they construct letters) is surprisingly constant, and is normally able to be located within a reasonably well-defined space of historic hands – Gothic, semi-Gothic, hybrida, mercantesca, Humanist, etc. Hence, the real problem here is arguably that this palaeographic starting point has failed to be determined.

Hence, I would say that looking at individual words is arguably the last thing you should be doing: instead, you should be trying to understand (a) how individual letters are formed, and (b) which particular letter instances are most reliable. From there, you should try to categorise the hand, which should additionally give you some clue as to where it is from and what language it is: and only then should you pass the challenge off from palaeography to historical linguistics (i.e. try to read it). And so I would say that attempting to read the marginalia without first understanding the marginalia hand is like trying to do a triple-jump but omitting both the hop and the skip parts, i.e. you’ll fall well short of where you want to get to.

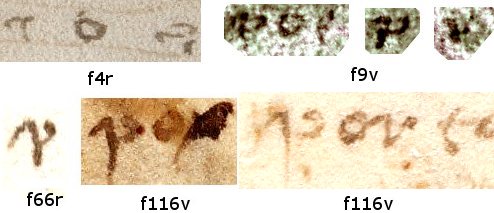

So let’s buck a hundred years’ worth of trend and try instead to do this properly: let’s simply concentrate on the letter ‘a’ and and see where it takes us.

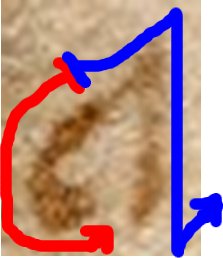

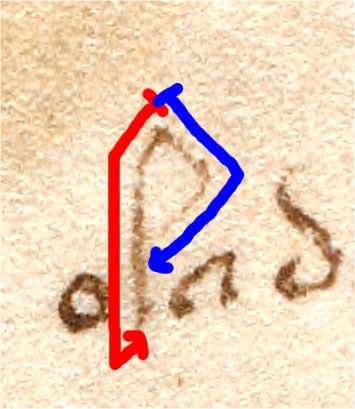

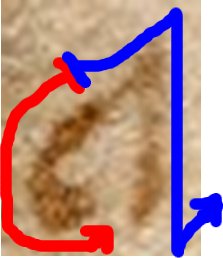

To my eyes, I think that a[5], a[6], and a[7] show no obvious signs of emendation and are also consistently formed as if by the same hand. Furthermore, it seems to me that these are each formed from two continuous strokes, both starting from the middle of the top arch of the ‘a’. That is, the writer first executes a heavy c-like down-and-around curved stroke (below, red), lifts up the pen, places it back on the starting point, and then writes a ‘Z’-like up-down-up zigzaggy stroke (below, blue) to complete the whole ‘a’ shape. You can see from the thickness and shape of the blue stroke that the writer is right-handed: while you can see from the weight discontinuity and slight pooling of ink in the middle of the top line exactly where the two strokes join up. I think this gives us a reasonable basis for believing what the writer’s core stroke technique is (and, just as importantly, what it probably isn’t).

What this tells us (I think) is that we should be a little uncertain about a[4], (which doesn’t have an obviously well-formed “pointy head”) and very uncertain about a[1], a[2], and a[3] (none of which really rings true).

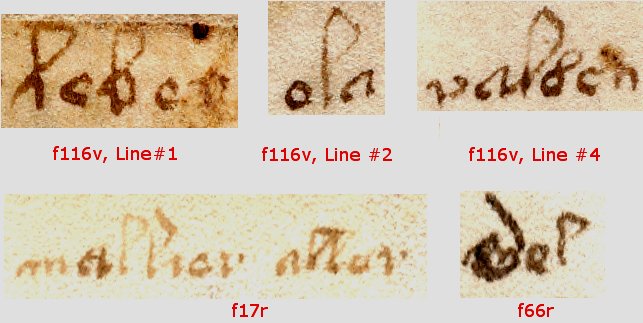

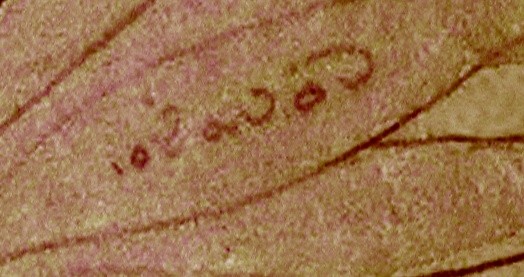

My take on all this is that I think a well-meaning VMs owner tried hard to read the (by then very faded) marginalia, but probably did not know the language it was written in, leaving the page in a worse mess than what it was before they started. Specifically: though “maria” shouts original to me, “oladaba8” shouts emendation just as strongly. Moreover, the former also looks to my eyes like “iron gall ink + quill”, while the latter looks like “carbon ink + metal nib”.

Refining this just a little bit, I’d also point out that if you also look at the two ascender loops in “oladaba8″, I would argue that the first (‘l’) loop is probably original, while the second (‘b’) loop is structured quite wrongly, and is therefore probably an emendation. And that’s within the same word!

The corollary is simply that I think it highly likely that any no amount of careful reading would untie this pervasively tangled skein if taken at face value: and hence that, for all his persistence and careful application of logic, Elmar has fallen victim to the oldest intellectual trap in the book – of pointing his powerful critical apparatus in quite the wrong direction. Sorry, Elmar my old mate, but you’ve got to be dead careful with these ancient curses, really you have. 🙂