[Here are links to chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Enjoy!]

* * * * * * *

Chapter 2 – “Game On”

Vivid dreams of a towering manuscript library on fire: the Renaissance inks and paints boil, become gas and swirl upwards into an angry elemental wind, textual spirits entombed for centuries but now set free to roam the atmosphere, their haunting transmuted into a gigantic elemental pall above New Haven, a Jovian minium spot written upon the Earth’s skies, a full stop in the book of the sky for many-parsec-distant alien telescopes to read…

“Hey, Mr Graydon Harvitz! I nearly didn’t recognize you!”

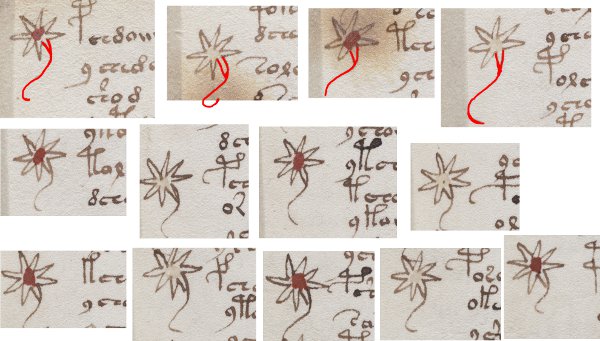

He started from his mid-day café reverie, nearly knocking his second half-cold latte over onto the sprawl of Voynich Manuscript scans as he half-rose, no less surprised by the sensation of his newly-shaven chin on his fingertips than by Emm’s voice.

“Yeah, well, what with my committee appearance coming up, it was time I cleaned up my act. A bit, anyway.”

Emm reached over to his shoulder, her long fingers swiftly transcribing the diagonal weft and weave of his grandfather’s ancient twill jacket, one of the few things Graydon had inherited. She paused for a second longer than he expected, reading the material’s texture as if it were a familiar book, her eyes briefly absent from the room. “Ah”, she said, “you like antiques as well”.

“When history surrounds you, you can’t really avoid it”, he replied grimly. But the truth was, he wore it in a superstitious half-hope that his grandfather’s whisky-soaked ghost might lend a hand on those occasions when he particularly lacked cryptographic inspiration. Which had been… most of the time this last few months. “Hungry?”

“As a horse – any protein-rich House Specials on today?”

“Naah”, he replied, “it’s all carbohydrates à la mode. But their Club Sandwich is pretty good.”

“Good call!”, she smiled, “I’ll be the hunter-gatherer, back in a minute…”

Graydon watched with no little curiosity as she lightly sashayed across to the counter, attracting both jealous and covetous eyeballs from the other customers as she went. Yet… even though Graydon had survived his epic (and admittedly much-delayed) battle with the razor this morning, he still felt like nothing whereas Emm really was something: where was the balance in the equation? What was in it for her? And moreover…

“What exactly does a cleaner do?” he asked as she carefully squeezed a fresh latte and her cappucino into two of the polygonal gaps between the printouts on the table.

“Well… we clean things – old things. Such as your favourite manuscript. The Beinecke’s curators have put off fixing it up for years, but let’s face it, the Voynich does need a bit of TLC, right?”

“I guess so”, he said. “I must admit my heart’s in my mouth every time I have to unfold the rosettes page. On balance, I’d prefer my tombstone not to say ‘the idiot who trashed the VMs‘.”

“Just so you know, sorting it all out is my next job, once ze feelm crew ‘az returned to La Belle France. Their director has already annoyed Mrs Kurtz, so I don’t think they’ll be here long.” She snatched a brief sip of her coffee, looking sideways through the café’s glass front. “Technically, I should just be able to get on with it, but… I’m going to need your help.”

Graydon exhaled relief as a smile rolled across his face. “And there I was thinking it was my eyes you were lusting after.”

“No, it’s your mind, you fool. Ordinary manuscripts are easy to tidy up because everything has its place. But in the case of the Voynich, I’d prefer my tombstone not to say ‘the idiot who wiped the code off the VMs‘. Without knowing what might be hidden where, being a cleaner isn’t such an easy gig.”

“Ordinarily”, he said, leaning forward conspiratorially, “I’d be a sucker for a beautiful woman so blatantly calling me to adventure, but… I also have the not-entirely-small issue of a ticking clock and a funding gun pointed at my head. And it’ll probably be no big surprise to you that my work on the manuscript is not quite as advanced as had been hoped.”

“So… is that a yes or a no?”

“Actually, as with everything else with the Voynich, it’s an ‘I-don’t-yet-know‘. I need to figure out in my mind whether hanging out with a supermodel doing cool codicology is worth risking my PhD for.”

“OK, no problem”, Emm said, quickly resting her forehead forwards onto her hand. Despite the amused self-deprecating smile on her face, Graydon could not help but notice a wave of stress flash through her eyes. “Maybe it’s not an either-or thing. Anyway, I’m just dying to ask you – what is that bulge in your pocket?”

“Jeez”, Graydon gagged,”what finishing school did you go to?”

“No”, she sighed, “not your pants, your jacket. If – as I’m pretty sure – it’s pre-1950, it really shouldn’t have a purely decorative pocket on the front. So… what’s it for?”

Graydon looked down at it as an oddly restrained silence fell over him: even though he’d worn his grandfather’s jacket countless times, he realised that he’d never properly looked at it before.

“Come on, then, pass it over”, she hustled, getting out a pair of white cotton gloves, a small ruler and a tiny flashlight from her Biba chainmail clutch bag. “I’ll have a closer look. Do you have a cameraphone?”

“Errr… yes I do”, he said, taking his Nokia out of the jacket as he passed it over the table to Emm, her eyes alive with the detail. “Though, I haven’t actually used it yet.”

“Here’s your chance to learn. You’ll need to photograph this seam here before and after I cut the thread, so I can restore it later.” Shining her light on the top seam with the ruler placed alongside it, she waited impatiently while Graydon haltingly navigated through the phone’s Byzantine user interface all the way to its camera submenu. At the clatter of the fake shutter sound effect, she lurched into action, selecting a microscopic pair of scissors from a diamante-studded Swiss army knife. One deft snip later, she was tweezing out the single long thread that had fastened the top edge in place for God-knows how many decades.

“Keep photographing, Gray… yup, we’ve got a hot one for you, Penny…”

The waiter arrived with their Club sandwiches, but Graydon slid them to one side of the table: for all their previous hunger, suddenly neither had any appetite for food at all.

At first, all they could see was a sliver of a pale brown edge: but this grew one tiny fraction at a time until Emm had finally pulled out a small scrap of aged parchment, covered in fingerprints and dirt. At its top was an inventory reference written in a mid-Victorian European copperplate hand – but in the centre there was an 8×8 table of unusual letters.

Up until now, these curious letter-forms had – for all their study – been unique to a single historical document.

But not now.

Unmistakeably – incredibly – the grid contained letters from the Voynich Manuscript.

“Game on!”, moaned Graydon, shaking his head in disbelief. “Game on!”

“Wow”, gasped Emm, her mouth dry with the tension, “even I didn’t really think codicology could beat sex.”

“But… maybe it’s not an either-or thing?”