On the morning of 1st December 1948, a man was found dead on Somerton Beach, not far from Adelaide, South Australia. Despite six decades of probing, his identity, his history and even his cause of death still remain undetermined.

At the time, the police investigation and Coronial Inquests into this “Somerton Man” cold case yielded thousands of facts and observations, though frustratingly few of these seem to connect together in any obviously coherent way.

For decades, the Somerton Man case was as unknown as the man himself, covered only occasionally by newspaper or magazine articles. Internet accounts typically presented it more as a Believe-It-Or-Not oddity than as a genuinely interesting historical cold case.

Hence for a very long time indeed the Somerton Man was a mystery wrapped in ignorance, and surrounded by often extravagantly melodramatic theorizing.

1. The Evidence

Yet in recent years the quality of the evidence available has dramatically improved. In 2010, Gerry Feltus – a retired policeman, who had covered the case during his time in the South Australian police force – wrote and published “The Unknown Man”, a detailed account of the Somerton Man case.

What Feltus set out to do with the book was to cover the facts as reliably as he could without straying into the murky realms of speculation: he discloses his opinions in only a handful of places. The book also strays only occasionally into the realm of the hypothetical, preferring to stick with the tangible and actual as far as practical.

Another person who has taken a special interest is Professor Derek Abbott of the University of Adelaide (the fact that his wife is directly related to one of the key people involved undoubtedly has great personal relevance to him). His major research contribution has been to amass a large collection of primary and secondary evidence relating to the Somerton Man (including the Coronial Inquest), and to make it freely available on the Internet.

Interestingly, Derek Abbott managed to retrieve some hairs embedded into a plaster cast of the Somerton Man’s body taken in 1949. A spectroscopic analysis of one of these hairs carried out by Abbott’s students revealed that the dead man had been exposed to alarmingly high levels of lead a few weeks before his death, though the full implications of this analysis have yet to be drawn out. Abbott’s legal attempts to have the Somerton Man exhumed (for the purposes of carrying out a detailed DNA analysis) have so far proved unsuccessful.

Finally: another extremely useful support for researchers has been Trove, the National Archive of Australia’s searchable set of scans of old Australian newspapers. It is important to stress that research into the Somerton Man would be extraordinarily difficult without this exemplary (and completely free) online resource.

As a result of all this, research into the Somerton Man cold case has switched round to a position diametrically opposite to where it was just a few years ago, insofar as researchers now have not too little evidence to deal with, but arguably too much.

In short, it seems likely to me that we already know enough to solve the mystery of the Somerton Man, if we could but look at the evidence from the right vantage point.

2. The Events

From ticket stubs found on the man’s body, we know that on 30th November 1948 (the day before he was found dead) he bought a railway ticket from Adelaide to Henley Beach (an Adelaide beach suburbs) but did not use it: and that he had instead caught an 11:15 bus from near Adelaide Station to Glenelg, a largely residential suburb close to Somerton Beach.

Further, there were reports that a similarly dressed man had been seen on Somerton Beach on the evening of that same day: and also (as dramatically revealed in Gerry Feltus’ book) that someone had been seen carrying a man (possibly drunk, possibly ill, possibly dead) near Somerton Beach late in that evening – again, perhaps it was the Somerton Man, and perhaps it wasn’t.

The Somerton Man’s cause of death appeared sudden but its cause defied simple explanation. And even though bleeding was found in his stomach (which suggested convulsive vomiting), no vomit was found near the body, and the man’s shoes were spotlessly clean.

Post mortem, blood had pooled near the back of his head (suggesting that he had lain with his head as the lowest point of his body for some hours after death): yet he was found in a position with the head propped up (so it was instead nearly the body’s highest point). There is therefore a strong likelihood that his body had been consciously posed after death (though Derek Abbott asserts that other explanations are possible).

As for the possessions on his person: he had no hat (which was unusual for the era), no wallet, no ration card, no id card, and no money, while his clothes had no labels or tags that could identify him. The trail had gone cold.

3. The Suitcase

However, a fortnight later, police found a suitcase that had been deposited in Adelaide Station’s Left Luggage room around 11am on the morning of the 30th November but which had not been collected: and were able to connect it to the dead man.

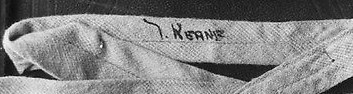

This contained many mismatched items of clothing and items that resembled a semi-improvised stencilling kit, but the only identification these offered was the name “T KEANE” or “T KEAN”. A police search found no missing person with that name.

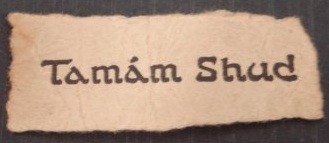

Also, a further mystery opened up: while examining the dead man’s clothes some time later, a small rolled up piece of paper ripped out from a printed book was found tucked inside a fob trouser pocket. Oddly, what was printed on that piece of paper was the Persian phrase “Tamam Shud” – “The End” (broadly speaking).

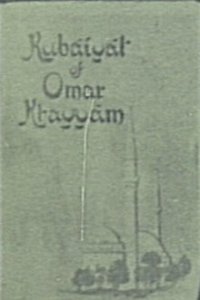

The police determined (after a while) that these were the last two words in a famous (and much-printed) book of poetry: “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam”. But nobody had a clue as to why this piece of paper was in the dead man’s pocket, or what possible message or signal its presence might indicate.

At this point, even though the Somerton Man’s stage had many props, it was still devoid of any supporting actors, so to speak. But this was about to change.

4. The Rubaiyat

When the first Coronial Inquest was reported widely in the papers, the police used the opportunity to put out a request to the public for anyone to get in contact with them if they had found or seen a copy of the Rubaiyat from around six months previously with the “Tamam Shud” removed from its inside back page.

Amazingly, someone had: a “Ronald Francis” (the alias used in Gerry Feltus’s book, the man’s real name has never been disclosed).

While the man’s car had been parked in Jetty Road in Glenelg, his brother-in-law had found a copy of the Rubaiyat on the floor by its back seat, and had put it into the glove compartment, thinking it was probably the man’s. Six months later, that Rubaiyat was still in the glove compartment: and it turned out to have had the “Tamam Shud” ripped out from the back by hand, just as the police had described.

According to the Adelaide Advertiser, 25th July 1949, “Ronald Francis” told Detective-Sergeant Leane that this had happened round about the time of the Parafield air display, which was a huge air event held just outside Adelaide on 20th November 1948 – ten days before the Somerton Man’s death.

The man told police that he “had known nothing about the much-publicised words “Tamam Shud” until he saw a reference to them on Friday”; and so the assumption was that the Rubaiyat had been dropped into the back of the car through the rear car window, perhaps by someone trying to get rid of it in a hurry.

“Ronald Francis” further asked the police not to reveal his name, saying that if they did, he would be “hounded” by the curious-minded.

Gerry Feltus knows “Ronald Francis”‘s identity and has talked with him and his family a number of times. I would add that even though the man’s account seems to have been refined since the initial Adelaide Advertiser report, Feltus remains in no doubt that “Ronald Francis” had nothing to do with the Rubaiyat, and that his car had been selected entirely at random.

5. The Cipher

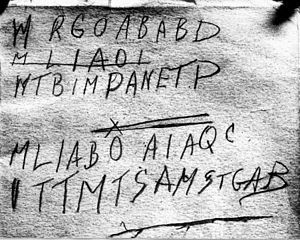

Intriguingly, it quickly turned out that the Rubaiyat had yet further secrets: that even though its soft rear cover page had been removed, indentations from writing that had been made onto that back cover were still faintly visible on the back end page.

What seems to have happened is that an investigating officer noticed that there were indentations on this end page, and started marking them out with a pencil, but quickly stopped; a photograph of this page (probably UV or infrared) was then taken (probably by top police photographer Jimmy Durham) and fixed onto photographic paper; the faint letters were then traced on top of that photograph by what appears to be a laundry pen; and then the over-written photograph was then photographed.

We have only a single reasonable quality image of the page, which was held in a newspaper archive (but it now seems likely to have been destroyed, leaving only a JPEG scan in the newspaper’s digital archive). [I have tried to contact Jimmy Durham’s family to see if they might have any of his pioneering forensic photographs; and it is also possible that the Australian Army or Navy might have a copy of the photograph sent to Eric Nave: but all these avenues have so far been unsuccessful.]

What was revealed by this was several lines of mysterious cipher-like letters, and either one or two phone numbers (though it is still unknown which). This was quickly passed on to a well-known codebreaker (who was, without any real doubt, Captain Eric Nave): he determined that the letters seemed not to be a code or a cipher, but were instead an acrostic – the initial letters of a sequence of words.

Further, Nave deduced from the statistics that the language of the sequence was very probably English, but was unable to take this line of reasoning any further – there simply wasn’t enough known about the rest of the case to draw any strong inferences.

What might these lines contain? Speculation has included “Strine poetry” (because it was on the back cover of a book of poetry), a set of directions, military abbrevations and even enciphered musical notation: but despite numerous such ingenious attempts to tease out the meaning, none seems close to a definitive answer.

6. The Nurse’s Phone Number

However, when police looked up one of the phone numbers (or perhaps the only phone number, depending on which account you believe) that they had found on the Rubaiyat’s end page, they discovered it was that of Sister Jo Thomson (née Jess[ica] Harkness), a nurse who had recently moved to Glenelg. Her house was a mere five minutes’ walk from where the Somerton Man’s body had been discovered.

Even though the nurse identified herself to police as “Mrs Thomson”, her partner Prosper McTaggart Thomson (better known as “George”) was at that time still married to his first wife. (They married in 1950 after his divorce had been finalized.)

She told police she knew nothing about a Rubaiyat, though she had once given a copy to a man called Alf Boxall. (Oddly, she had signed her name “JEstyn”, for reasons that remain unknown). However, the excitement this caused in the police investigation team quickly abated when Boxall was found to be very much alive.

By this time, the Somerton Man had been buried: but a plaster cast had been made of his head and upper torso by taxidermist Paul Lawson. When Jo Thomson went to the morgue to see it, Lawson reported (in a 1978 TV documentary) that she seemed visibly shocked by what she saw. Even so, she did not identify the body to the police.

Jo Thomson was not openly named as the nurse until an Australian TV “60 Minutes” episode in 2013, some six years after her death. In this, Jo’s daughter Kate revealed that her mother did know the identity of the Somerton Man; that her mother thought the whole affair was above “a State Police level”; but that she would not say more.

More to come in Part 2…