Some interesting Cipher Mysteries comments arrived here today from “RT”, prodding me to take a second look at something I nosed around a while back (but then promptly forgot to blog about). Here’s what he wrote:-

RT comment #1: “I think the SM was married to Jessica.”

RT comment #2: “Has anyone thought that she could have been Mrs J E Styn. Or Van Styn? […]”

RT comment #3: “I along with others have always thought she was married to him. I think that for some reason she did a runner from him met Prosper and changed her name. He tracked her down and things went sour. That is only my opinion but you need proof. I also am very certain that Robin is the SM’s son. I think that Prosper was aware of this and accepted it. It worked well for him as his parents were very wealthy and a son would enable him to collect an increased inheritance.”

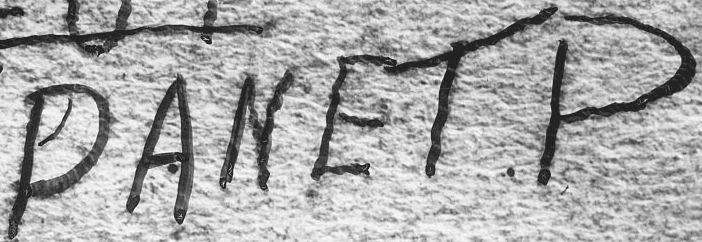

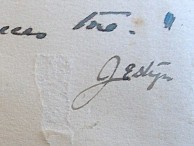

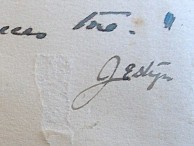

For all the ideas, notions, and speculations in there, this is a splendidly romantic secret history, albeit one woefully short of actual facts (which RT freely admits). But let’s look again at the primary evidence we do have – the “Jestyn” signature in the copy of the Rubaiyat given to Alf Boxall:-

According to Gerry Feltus: when Jessie met Boxall in 1944, she knew that he was married and had two children (his second child, a daughter called Lesley, had just been born), and she had his address in Maroubra: so I think that quite why she felt the need to sign herself with a different name “Jestyn” (or “JEstyn” as Feltus writes it) in the Rubaiyat is an open (and slightly perplexing) question. And there’s definitely a gap between the “JE” part and the “styn” part.

Another unexplained question from this time is why Jessie changed her name to Thomson several years before her husband-to-be’s divorce came through. According to RT’s (admittedly unverified) story, this was because she was ‘on the run’ from her previous partner / husband: but all we actually know for sure is that she “terminated her employment as a nurse in Sydney” in 1946, moved to Mentone near her parents, and then moved to Adelaide in early 1947, where she gave birth (to Robin) in the middle of 1947, all (again) according to the ever-reliable Gerry Feltus.

Could it be, then, that the secret history of this signature is that it is actually “J. E. Styn“, and that Jessica had taken her earlier partner’s surname? I wondered about this a while back, and so did various searches (Trove etc) for “Styn” that all turned up nothing at all promising. It all seemed to be a blank.

But today, I did another trawl over broadly the same set of archives and found a single reference I had previously missed to a Willen Styn. It’s “NAA: PP14/3 DUTCH/STYN W”, containing “STYN Willen – Nationality : Dutch – [Application Form for Registration as Alien]”, dating from 1916-1920, item barcode 5143479 in Perth. If you want to see the catalogue entry, go to the National Archives of Australia, click on RecordSearch, and then search for Willen Styn. I’ve already ordered a copy of the actual record, and will let you all know when it arrives.

Note that the PP14/3 series of archives is “the Register of aliens maintained under War Precautions (Aliens Registered) Regulations 1916”, i.e. a list of foreign nationals in Australia at the time of WW1 (presumably because Styn was Dutch). The Australian archives have plenty of related immigration files from the same period (e.g. PP14/1, which I went through the index of just in case there was some kind of misspelling of Styn in there, but to no avail).

So… I’ll say it. If “Jestyn” should properly be read as “J. E. Styn”, then might the Somerton Man be the somewhat-off-the-radar Dutchman Willen Styn? Let’s go and look for some evidence, see what we turn up.

Right now, I have a sneaking suspicion that he may turn out to be even harder to track than dear old Horace Charles Reynolds… but we shall see! So this is your cue: Cipher Mysteries research legions, please descend upon the collected Australian archives and see if you can find anything – anything at all! – about the mysterious Willen Styn. Good hunting! 🙂