Italian scientists claim to have solved two mysterious deaths from the Quattrocento: those of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and Agnolo Ambrogini, two big-brained Florentines at Lorenzo de’ Medici’s court who suddenly passed away within only a few weeks of each other in 1494.

Though some historians had conjectured the pair might have died of syphilis, the contemporary rumours of poisoning have apparently now been supported by the high levels of arsenic, mercury and lead found (very, very post mortem) “in Pico’s tissues and nails”, the report goes on. All fascinating forensic stuff, I’m sure. (With slightly more in the Telegraph’s coverage).

But… permission to speak, please, Mr Italian Scientists? The 15th century in Italy was full of hazards, no less from your friends than from your enemies. For example, the culinary fashion was for really undercooked meat (and lots of it), which can (quite literally) be a recipe for disaster – and whenever anyone died suddenly, the jabbing finger of retribution usually pointed at anywhere but the kitchen.

For the rich (i.e. those who could afford apothecaries), another major source of death-by-(mis)fortune was the arsenic-, lead- and quicksilver- (i.e. mercury-)based medicines that were sometimes in favour. I would say that the best thing about the medieval cure “theriac” was that its large number (often 70+) of ingredients usually meant that none of them came in a strong enough dose to kill you.

Put bluntly, I would be thoroughly unsurprised if other bones from similar Medici courtiers happened to exhibit precisely the same tox profile: but without actually killing them. And there are many reports of poisoning plots that failed – different groups used different poisons (the Borgias favoured inorganic ones, as I recall), often ineffectively. Did the two men’s similar deaths mean they shared the same enemy, or just the same apothecary and cook?

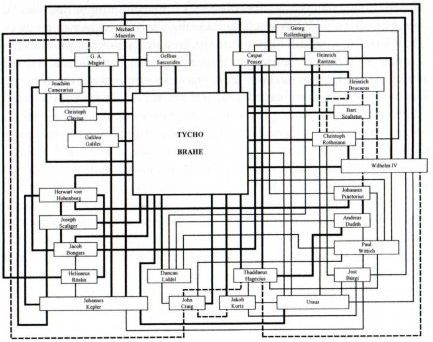

Merely pointing to the arsenic etc isn’t enough to tell the whole story: and this is why I sometimes despair at the sight of scientists’ trying to do history. Different types of evidence (and inquiry) yield different and complementary types of story, and it is usually only by linking all these together that the whole narrative emerges. These days, history is multimedia, or it is nothing.

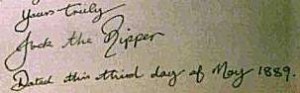

Here, “historical documents that have only recently come to light” (suggesting that Piero de’ Medici was angered by Pico’s connection with mad preacher Savonarola) ought to give the inevitable documentary a spin in the right direction. However, only in Hollywood’s cheesier fringes might someone think that writing “kiiiiiill hiiiim” in a letter would be a good idea. Will the archives really have enough to hold it all together?

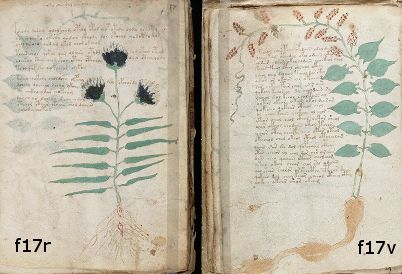

All the same, if someone could point to some coded letters written in 1493-1494 by Pico della Mirandola’s enemies, well, then we might just be in business… 😉