For me, there’s something wonderfully apposite about the “Renaissance Faces: Van Eyck to Titian” exhibition currently downstairs at the Sainsbury wing of the National Gallery in London. Having just read and reviewed the revised (2006) edition of David Hockney’s “Secret Knowledge” book, the opportunity of looking really up close at some of the key pictures on Hockney’s wall was something I simply had to jump at.

The first obvious biggy there was Van Eyck’s 1434 Arnolfini couple, a fabulous picture by any standards. But was it eyeballed (painted from life in the conventional manner), projected (according to some abstract mathematical perspective scheme), traced (from some kind of clever optical projection, something like a curved mirror), gridded (through some kind of fixed eye-position gridded frame) or some ad hoc mix of all the above? There are plenty of (what seem to me) obviously eyeballed features, such as the dog and, indeed, the Arnolfini couple themselves: yet while Hockney’s key feature (the ornate chandelier) is an impressive piece of craft, the level of draughtsmanship apparent in the whole picture is extremely high (for example, Hockney’s book fails to stress the unbelievably tiny size of the two characters coming through the door reflected in the convex mirror on the back wall). Perhaps Hockney has got it right that Van Eyck did make us of some kind of technological assistance: but I really couldn’t stand up and say that this could only have been via optical trickery. In my experience, artists are highly ingenious people who will apply whatever tricks they can conjure up to the particular problem of depiction or representation in their mind at the time.

In short, “not proven”.

The second biggy was Giovanni Bellini’s scintillating, (literally) silky-smooth 1501 portrait of Doge Lorenzo Loredan. David Hockney places great value on the huge advances in rendering complex folded fabrics that artists made during the fifteenth century, followed by the similar advances made in rendering shiny objects (most notably polished armour and glass) during the sixteenth century. Cleverly, though, the exhibition curators placed Bellini’s Doge close to the 1454 bust of Niccolo Strozzi by Mino da Fiesole, where the pattern in the (probably silk velvet) fabric had been subtly rendered in stone. And I think this holds the real point about the shimmering Doge: that to me, it comes across not as having been executed within the tradition of painted portraiture, but instead as having been sculpted from light, in a way that is unnervingly close to cinematographic. Yet simultaneously, of all the portraits in the exhibition, Bellini’s Doge was – for all its svelte finesse and brilliant sheen – one of the least “alive”, in much the same way that ultra-high-speed photographs manage to sever their association with the sheer physicality of the subject.

The single technique that transformed during the 15th century involved a brand new way of seeing: unlearning what you would expect to see in a scene, and instead allowing yourself simply to be guided by the light. Painters had always painted what they saw, but as they now saw the world in a quite different way, the paintings they produced radically reflected that new vision: and paint technology changed (from egg tempera to oils) just as radically to support this vision.

Did some kind of projective / optical technological trick help (if not drive!) this Quattrocento sea-change in artistic approach and technique? David Hockney is convinced that there had to have been, while Martin Kemp remains agnostic (if not actually unconvinced). My own opinion is simply that unpicking the multiple overlapping revolutions that occurred during that period is a far trickier job than Hockney would like it to be: and that he is building his case on a relatively small set of features in paintings by painters with almost peerless technique.

But move on to the sixteenth century, and I think the whole question is thrown open again. There you have artists openly working with convex mirrors (such as Parmigianino’s self-portrait in a convex mirror of 1524), a slowly growing body of theoretical literature on the camera obscura, and the emergence, later in the century, of a certain look (tenebrous/flat backgrounds, sharply lit, optically dramatic, but with an often-unconvincing collage aspect) whose distinctive filmic virtuosity almost inevitably impresses the eye. Was this merely the Mannerist artistic fashion of the moment, or the necessary byproduct of an optical assist?

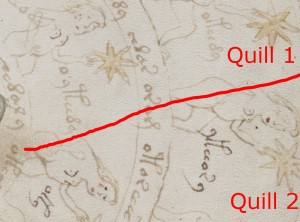

In this regard, one tiny detail in the National Gallery’s exhibition caught my eye. The picture called “Portrait of a Lady with Spindle and Distaff” by Maertin [Martin] van Heemskerck (dated 1529-1531) has an ultra-complex foreground object – an ornate spinning wheel on a decorated base. But there is one place where the picture appears (like a badly assembled railway station poster) to have been stuck together incorrectly. Unfortunately, I didn’t have my camera with me, and it’s right on the limit of what you can comfortably see in an A4-sized reproduction. Here, I’ve taken a small piece from the website of the Museo Thysen-Bornemisza in Madrid (which owns the picture), tweaked the brightness and contrast, and added an unsubtle red arrow to show where I think the collage-like break occurs:-

Is this (a) another possible smoking gun to add to Hockney’s list, (b) a faithful reproduction of a flaw in the actual marquetry, (c) a slip of the painter’s brush, or (d) a subtle mistake made by a later restorer? I’m just flagging it here, I’ll leave it to others to settle the question. If you’d like to have a look for yourself, the exhibition continues until the 18th January 2009 – it’s £10 to get in, and worth every penny (in my opinion).

Incidentally, van Heemskercks’ picture is reproduced on p.131 of the hefty (but beautiful) exhibition catalogue, which I’ll be reviewing in a few days’ time.

PS: Voynich completists will probably enjoy Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s “Vertumnus” fruit-and-flower portrait of Rudolf II, as well as Holbein’s “Ambassadors” (with its array of finely-rendered Renaissance gadgetry), both also in the same exhibition! 🙂