An off-blog email exchange about the Grolier Club (where Wilfrid Voynich’s estate bequeathed eight boxes of papers relating to his book business in America) nudged my memory about a minor player on the 20th century Voynich stage…

When Voynich researcher Richard SantaColoma visited the Grolier Club back in May 2008, he trawled through these boxes (Box 6 in particular) for anything unexpected: he very kindly wrote up his notes and passed them on to the Journal of Voynich Studies, which posted them on its website.

There are some scans of letters (and extracts of letters) sent by William Romaine Newbold: and Ethel Voynich’s handwritten notes on Voynich botany: but probably the most interesting thing is a set of short research notes from Anne Nill’s ring binder in Box 6.

On page 2, there’s an August 1917 letter from ‘Edith Richert’ to Wilfrid Voynich, asking: “I should be glad to know your reasons for believing that the symbols vary according to their position. I have my own reasons. I should like to see whether they agree.”

WMV replied (in September 1917) that “I have no reasons for believing that the symbols vary to their positions, as I know nothing about cipher. But it was the opinion of two or three European professors.”

I was particularly struck by this clear-sighted observation (by Richert and the European professors): thanks to modern computer transcriptions, this kind of thing is now plain to see – but all the same, this was only 1917.

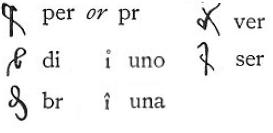

Who was this “Edith Richert”? Actually, this was Edith Rickert (1871-1938), who worked at the University of Chicago, and worked very closely with our old friend John Matthews Manly, co-authoring numerous books with him, and spending sixteen years on “a monumental undertaking of scholarship, critical analysis, and data collection” – a critical edition of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales.

John Matthews Manly and Edith Rickert, 1932

John Matthews Manly and Edith Rickert, 1932

There’s much more on their working relationship on this U. of Chicago webpage here. However, exhausted by the epic scale of what they were trying to achieve, Rickert died just before publication of the first volume: though Manly lived long enough to see the project completed, he too died soon afterwards.

What I find slightly unnerving is that what Manly and Rickert were attempting to do for the Canterbury Tales (detailed palaographic and codicological analysis, examining every page of every manuscript in person looking for otherwise unseen clues to its secret history) is precisely what we are trying to do for the Voynich Manuscript. But all the same, it took them (and a funded team of graduate students and collaborators) 16 years, and the effort pretty much killed them both. Hmmm… makes you wonder how much of a chance of success we actually stand, doesn’t it?

The punchline here is that Manly and Rickert actually worked together breaking World War One codes – yes, she was an Allied cryptologist. There’s much more on her life here, and a copy of the book “Edith Rickert: a memoir” (1944) by Fred Millett is online here.

But, hold on a minute! I normally don’t like counterfactual histories, but… if William Romaine Newbold hadn’t wrecked the credibility of our “Roger Bacon Manuscript”, what are the chances that Manly and Rickert in 1924 might have instead chosen that as their subject for study in preference to Chaucer? Really, who’s to say?